- Home

- Cory Doctorow

The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow Page 7

The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow Read online

Page 7

There was a small crowd hanging around the Carousel as I got back to it. They weren’t exactly blocking the way, more like milling about, chatting, being pastoral, but always in the vicinity of my home. Someone came out of my outhouse: Brent. A moment later, I spotted Sebastien.

“We were hoping for a ride,” he said. “Brent was asking about it again.”

Uh-huh. “And these other people?”

My antenna wasn’t radiating sarcasm or anger, though my voice was full of both. He believed the evidence of his antenna and continued to treat me as though I was calm and quiet.

“Other riders, I suppose.”

“Well, I’m not giving any rides today,” I said. “You can all go home.”

“Is it broken again?”

“No,” I said.

“Oh,” he said.

Brent and Tina wandered up. Brent looked at me with his head cocked to one side. “Hi, Jimmy,” he said. “We want to go inside and ride around.”

“Not today. Try me again in a week.”

Tina put a hand on my arm. It was warm and maternal. It made me feel weird. “Jimmy, you know you have to bring her around to council if she’s going to stay here. It’s the way we do things.”

“She’s not staying,” I said.

“She’s stayed long enough. We can’t ignore it, you know. It’s not fair for you to ask us to pretend we didn’t see her. We all have a duty. Your friend can get the operation, or she can go.”

“She’s not staying,” I said. Neither am I is what I didn’t say.

“Jimmy,” she said, but I didn’t want to hear what she had to say. I shook off her arm and climbed the ramp up to my door, sliding it aside, stepping in quickly and sliding it shut behind me.

“Look, I’m a nest!” The entire pack had swarmed Lacey, perching on her arms, head, shoulders and chest. She was sitting in the front row of the theater, balancing. “These are some fun little critters. I can’t believe they lived this long!”

I shrugged. “Far as I can tell, they’re immortal.” I shrugged again. “Poor little fuckers.”

She shook off the pack. They raced around under the seats. They were starting to get squirrelly. I really should have been taking them out for walks more often. She came and gathered me in her arms. It felt good, and weird.

“What’s going on?”

“Let’s go, OK? The two of us.”

“You don’t mean out for a walk, do you?”

“No.”

She let go of me and sat on the stage. We were in the “future” set, which Dad said was about 1989, but not very accurate for all that. The lights on the Christmas tree twinkled. I’d wiki-tagged everything in the room, and the entry on Christmas trees had been deeply disturbing to me. All that family stuff. So … treehugger. Some of the wireheads did Christmas, but no one ever invited me along, thankfully.

“I don’t think that’s a good idea, Jimmy. It’s dangerous out there.”

“I can handle danger.” I swallowed. “I’ve killed people, you know. That last day I saw you, when they came for Detroit. I killed eight of them. I’m not a kid.”

“No, you’re not a kid. But you are, too. I don’t know, Jimmy.” She sighed and looked away. “I’m sorry about last night. I never should have—”

“I’m not a kid! I’m older than you are—just because I look like this doesn’t mean I’m not thirty-two, you know. It doesn’t mean I’m not capable of love.” I realized what I’d just said.

“Jimmy, I didn’t mean it like that. But whatever you are, we can’t be, you know, a couple. You can see that, right? For God’s sake, Jimmy, we’re not even the same species!”

It felt like she’d punched me in the chest. The air went out of my lungs and I stared at her, pop-eyed, for a long moment.

I felt tears prick at my eyes and I realized how childish they’d make me seem, and I held them back, letting only one choked snuffle escape. Then I nodded, calmly.

“Of course. I didn’t want to be part of any kind of couple with you. Just a traveling companion. But I can take care of myself. It’s fine.”

She shook her head. I could see that she had tears in her eyes, but it didn’t seem childish when she did it. “That’s not what I meant, Jimmy. Please understand me—”

“I understand. Last night was a mistake. We’re not the same species. You don’t want to travel with me. It’s not hard to understand.”

“It’s not like that—”

“Sure. It’s much nicer than that. There are a million nice things you can say about me and about this that will show me that it’s really not about me, it’s just a kind of emergent property of the universe with no one to blame. I understand perfectly.”

She bit her lip.

“That’s it, huh?”

She didn’t say anything. She shook her head.

“So? What did I get wrong, then?”

Without saying another word, she fled.

I went outside a minute later. My neighbors were radiating curiosity. No one asked me anything about the woman who’d run out of the Carousel and taken off. Her stuff was still in my little sleeping-space and leaned up against the stage. I packed it as neatly as I could and set it by the door. She could come and get it whenever she wanted.

The fourth scene in the Carousel of Progress is that late-eighties sequence. We had other versions of it in the archives, but the eighties one always appealed to Dad, so that was the one that I kept running most of the time.

Like I said, it’s Christmastime, and there’s a bunch of primitive “new” technology on display—a terrible video game, an inept automatic cooker, a laughable console. The whole family sits around and jokes and plays. Grandpa and Grandma are vigorous, independent. Sister and Brother are handsome young adults. Mom and Dad are a little older, wearing optical prostheses. Dad accidentally misprograms the oven and the turkey is scorched. Everyone laughs and they send out for pizza.

I always found that scene calming. It was supposed to be set a little in the future, to inspire the audience to see the great big beautiful tomorrow, shining at the end of every day (for a while, the theme of the ride had been, “Now is the best time of your life,” which seemed to me to be a little more realistic—who knew what tomorrow would be like?).

Dad believed in progress, I’ve come to realize. He made me because he thought that the human race would supplanted by something transhuman, beyond human. Like it would go, squirrel, monkey, ape, caveman, human, me. He was the missing link between the last two steps, the human who’d been modded into transhumanism.

But if Dad were alive today, he’d probably be learning from his mistakes with me and making a 2.0 version. Someone who made me look as primitive as I made Dad look. And twenty years after 2.0, there’d be a 3.0, a whole generation more advanced. Maybe twenty feet tall and able to grow extra limbs at will.

And in a thousand years, we’d still be alive, weird, immortal cavemen surrounded by our telepathic, shapeshifting, hyperintelligent descendants.

Progress.

I heard Lacey let herself in on the second night. I’d lain awake all night the first night, waiting for her to come back for her bedroll and her cowl. When she didn’t, I figured she’d found somewhere warm to stay. There had been a lot of treehouse seed in the air for the past four or five years, and the saplings were coming up now, huge, hollow root-balls protruding from the ground. They grew very fast, like all good carbon-sinking projects, but they had a tendency to out-compete the local species, so the wireheads chopped them down and mulched them when they took root. Still, you didn’t have to go very far into our woods to find one.

I spent the next day paying social calls on wireheads, letting their talk about crops and trade while away the hours, just spending the time away from home so I wouldn’t have to see Lacey if she came back for her things that day. But when I came home and said hello to the pack and made dinner, her pack was still by the door. At that point, I decided she wouldn’t come back for a while. Maybe s

he’d found a nice traveler to go caravanning with.

She let herself in quietly, but the pack was roused, and a second later I was roused too. My bedding still smelled like her. I was going to have to wash it. Or maybe burn it.

I sat up and padded through the gloom into the fourth scene. She was sitting in a middle-row aisle seat with her pack between her knees, watching the silent silhouettes of the robots in their Christmas living room.

I shrugged and turned it on. We watched them burn the turkey. They ordered out for pizza. They sang: “There’s a great big beautiful tomorrow/shining at the end of every day.” The Carousel rotated another 60 degrees and back to the beginning. The show ended.

“Safe travels,” I said to her.

She rocked in her seat as if I’d slapped her. “Jimmy, I have something I need to tell you. About that day in Detroit. Something I couldn’t tell you before.” She took a shuddering breath.

“You have to understand. I didn’t know what my parents were planning. They didn’t like you any more than your dad liked me, so I was a little suspicious when they told me to take my spidergoat and go and play with you over in the city. But things had been really tense around the house and we’d just had another blazing fight and I figured they wanted to have a discussion without me around and so they told me to do the thing that would be sure to distract me.

“I didn’t realize that they wanted me to distract you, too.

“They told me later that someone else had gone into town to lure your father away, too. The idea was the get both of you away from your defenses, to demolish your capacity to attack, and then to turn the wumpuses loose on the city until there was nothing left, then to let you go. But your dad got away, figured out what was going on, got into his plane and—”

She shut her mouth. I looked at her, letting this sink in, waiting for some words to come.

“They told me this later, you understand. Weeks later. Long after you were gone. I had no idea. They had friends in Buffalo who had the mechas and the flying platform, friends who were ideologically committed to getting rid of the old cities. They hated your dad. He had lots of enemies. They didn’t tell me until afterward, though. I was just … bait.”

I remembered how fast she had disappeared when the bombs started falling. And not into the mecha, which should have been the safest place of all. No, she’d gone out of the city.

“You knew,” I said.

She wiped her eyes. “What?”

“You knew. That’s why you scarpered so quickly. That’s why you didn’t get into the mecha. You knew that they were coming for us. You knew you had to get out of the city.”

“Jimmy, no—”

“Lacey, yes.” The calm I felt was frightening. The pack twined around my feet, nervously. “You knew. You knew, you knew, you knew. Have you convinced yourself that you didn’t know?”

“No,” she said, putting her hands in front of her. “Jimmy, you don’t understand. If I knew, why would I have come back here to confess?”

“Guilt,” I said. “Regret. Anger with your parents. You were just a kid, right? Even if you knew, they still tricked you. They were still supposed to be protecting you, not using you to lure me away. Maybe you have a crush on me. Maybe you just want to screw with my head. Maybe you’ve just been distracting me while someone comes in to attack the wireheads.”

She gave a shiver when I said that, a little violent shake like the one I did at the end of a piss. I saw, very clearly in the footlights from the stage, her pupils contracting.

“Wait,” I said. “Wait, you’re here to attack the wire-heads? Jesus Christ, Lacey, what the hell is wrong with you? They’re the most harmless, helpless bunch of farmers in the world. Christ, they’re practically Treehuggers, but without the stupid politics.”

She got up and grabbed her pack. “I understand why you’d be paranoid, Jimmy, but this isn’t fair. I’m just here to make things right between us—”

“Well, forgive me,” I said. “What could I possibly have been thinking? After all, you were only just skulking around here, gathering intelligence, slipping off into the night. After all, you only have a history of doing this. After all, it’s only the kind of thing you’ve been doing since you were a little girl—”

“Goodbye, Jimmy,” she said. “You have a nice life, all right?”

She went out into the night. My chest went up and down like a bellows. My hands were balled into fists so tight it made my arms shake. The pack didn’t like it. “Follow her,” I whispered to Ike and Mike, the best trackers in the pack. “Follow her”—a command they knew well enough. I’d used them to spy on my neighbors after arriving here, getting the lay of the land. “Follow her,” I said again, and they disappeared out the door, silent and swift.

I could watch and record their sensorium from my console. I packed a bag, keeping one eye on it as I went. I grabbed the pack’s canisters. They were too heavy to carry, but I had a little wagon for them. I piled them on the wagon, watching its suspension sag under the weight.

Ike and Mike had her trail. She headed into the woods with the uneasy gait of a weeping woman, but gradually she straightened out. She kept on walking, picking up speed, clipping on an infrared pince-nez when she came under the canopy into the real dark. I noted it and messaged Ike and Mike about their thermal signatures. They fell back and upped the zoom on their imaging, the picture going a little shaky as they struggled to stabilize the camera at that magnification.

She emerged from the woods into a clearing heaped high with rubble. I watched her sit down with her feet under her, facing it. She was saying something. I moved Ike up into mic range. She didn’t say much, though, and by the time he was in range, she fell silent.

The rubble stirred. Some rocks skittered down the side of the pile. Then a tentacle whipped out of the pile, a still-familiar mouth at the end of it. The mouth twisted around and grabbed up one of the larger rocks and began to digest it. More tentacles appeared, five, then fifty, then hundreds. The rubble shifted and revealed the wumpus beneath it.

It was the biggest one I’d ever seen. It had been twenty years since I’d last seen one of those bastards, and maybe my memories were faulty but this one seemed different. Meaner. Smarter. Wumpuses were usually bumblers, randomwalking and following concentration gradients for toxins, looking for cities to eat, mostly blind. This one unfolded itself and moved purposefully around the clearing, its wheels spinning and grinding. As it rolled, smaller wumpuses fell out of its hopper. It was … spawning!

It seemed to sense Ike and Mike’s presence, turning between one and the other. They were deep in the woods, running as cold as possible, camouflaged, perfectly still, communicating via narrow, phased-array signals. They should be undetectable. Nevertheless, I gave them the order to shut down comms and pull back slowly to me.

I stood out on the porch, waiting for them to rejoin me in the dark, hearing the sounds of the night woods, the wind soughing through the remaining leaves, the sounds of small animals scampering in the leaves and the distant frying-bacon sound of the wumpus and its litter digesting.

There was no chance that Lacey was doing something good with that wumpus. She had lied from the minute she met me in the woods. She had scouted out the wirehead city. She had gone back and reported to some kind of highly evolved descendant of the wumpuses that ate every city on the continent.

I had already been ready to go. I could just follow through on my plan, hit the road and never look back. The wireheads weren’t my people, just people I’d lived with.

If I was a better person, my instinct would be to stay and warn them. Maybe to stay and fight. The wumpus would need fighting, I knew that much.

I’m not a good person. I just wanted to go.

I didn’t go—and not because I’m a good person. I didn’t go because I needed to see Inga and find out if she really had the cure for my immortality.

Inga lived in the same house she’d grown up in. I’d gone over to play there, twenty ye

ars ago. Her parents had just grown new rooms as their kids had grown up, married, and needed more space. Now their place had ramified in all directions, with outbuildings and half-submerged cellars. I took a chance that Inga’s room would be where it had been the last time.

I knocked on the door, softly at first. Then louder.

The man who answered the door was old and grey. His pajamas flapped around him in the wind that whipped through the autumn night. He scrubbed at his eyes and looked at me.

“Can I help you?” His antenna radiated his peevish sleepiness.

“Inga,” I said. My heart was hammering in my chest and the sweat of my exertions, lugging the pack’s canisters across town, was drying in the icy wind, making me shiver. “I need to see Inga.”

“You know what time it is?”

“Please,” I said. “I’m one of her research subjects. It’s urgent.”

He shook his head. The irritation intensified. With all the other wireheads asleep, there was no one to damp his emotion. I wondered if he was souring their dreams with his bad vibes.

“She’s in there,” he said, pointing to another outbuilding, smaller and farther away from the main house. I thanked him and pulled my wagon over to Inga’s door.

She answered the door in a nightshirt and a pair of heavy boots. Her hair was in a wild halo around her head and limned by the light behind her and I had a moment where I realized that she was very beautiful, something that had escaped me until then.

“Jimmy?” she said, peering at me. “Christ, Jimmy—”

“Can I come in?”

“What’s this about?”

“Can I come in?”

She stood aside. I felt her irritation, too.

Her room was small and crowded with elaborate sculpture made from fallen branches wound with twine. Some of them were very good. It was a side of her I’d never suspected. Weirdly enough, being a wirehead didn’t seem to diminish artistic capacity—there were some very good painters and even a couple of epic poets in the cult that I quite liked.

Pirate Cinema

Pirate Cinema Walkaway

Walkaway Little Brother

Little Brother Someone Comes to Town, Someone Leaves Town

Someone Comes to Town, Someone Leaves Town The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow

The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow Super Man and the Bug Out

Super Man and the Bug Out For the Win

For the Win A Place so Foreign

A Place so Foreign Shadow of the Mothaship

Shadow of the Mothaship Return to Pleasure Island

Return to Pleasure Island Party Discipline

Party Discipline Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom

Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom Lawful Interception

Lawful Interception Homeland

Homeland Eastern Standard Tribe

Eastern Standard Tribe Chicken Little

Chicken Little I, Row-Boat

I, Row-Boat Makers

Makers Rapture of the Nerds

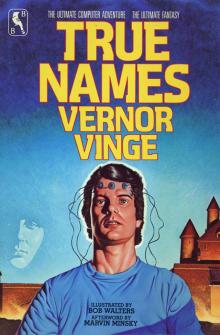

Rapture of the Nerds True Names

True Names