- Home

- Cory Doctorow

The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow

The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow Read online

CORY DOCTOROW

Winner of the John W. Campbell Award

Locus Award

Sunburst Award Electronic Frontier Foundation Pioneer Award

Prometheus Award

White Pine Award

“Doctorow uses science fiction as a kind of cultural

WD-40, loosening hinges and dissolving adhesions to

peer into some of society’s unlighted corners.”

—New York Times

“Doctorow demonstrates how memorably the outrageous

and the everyday can coexist.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Doctorow shows us life from the point-of-view of the

plugged-in generation and makes it feel like a

totally alien world.”

—Montreal Gazette

He’s got the modern world, in all its Googled, Friendstered

and PDA-d glory, completely sussed.

—Kirkus Reviews

PM PRESS OUTSPOKEN AUTHORS SERIES

1. The Left Left Behind

Terry Bisson

2. The Lucky Strike

Kim Stanley Robinson

3. The Underbelly

Gary Phillips

4. Mammoths of the Great Plains

Eleanor Arnason

5. Modem Times 2.0

Michael Moorcock

6. The Wild Girls

Ursula Le Guin

7. Surfing The Gnarl

Rudy Rucker

8. The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow

Cory Doctorow

9. Report from Planet Midnight

Nalo Hopkinson

© 2011 CorDoc-Co, Ltd (UK).

Some Rights Reserved under a Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License

This edition © 2011 PM Press

Series Editor: Terry Bisson

ISBN: 978-1-60486-404-5

LCCN: 2011927947

PM Press

P.O. Box 23912

Oakland, CA 94623

PMPress.org

Printed in the USA on recycled paper, by the Employee

Owners of Thomson-Shore in Dexter, Michigan.

www.thomsonshore.com

Outsides: John Yates/Stealworks.com

Insides: Josh MacPhee/Justseeds.org

CONTENTS

The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow

“Creativity vs. Copyright” 107

“Look for the Lake” Outspoken Interview with Cory Doctorow

Bibliography

About the Author

THE GREAT BIG

BEAUTIFUL TOMORROW

PART 1: A SPARKLING JEWEL

I PILOTED THE MECHA THROUGH the streets of Detroit, hunting wumpuses. The mecha was a relic of the Mecha Wars, when the nation tore itself to shreds with lethal robots, and it had the weird, swirling lines of all evolutionary tech, channeled and chopped and counterweighted like some freak dinosaur or a racecar.

I loved the mecha. It wasn’t fast, but it had a fantastic ride, a kind of wobbly strut that was surprisingly comfortable and let me keep the big fore and aft guns on any target I chose, the sights gliding along on a perfect level even as the neck rocked from side to side.

The pack loved the mecha too. All six of them, three aerial bots shaped like bats, two ground-cover streaks that nipped around my heels, and a flea that bounded over buildings, bouncing off the walls and leaping from monorail track to rusting hover-bus to balcony and back. The pack’s brains were back in Dad’s house, in the old Comerica Park site. When I found them, they’d been a pack of sick dogs, dragging themselves through the ruined city, poisoned by some old materiel. I had done them the mercy of extracting their brains and connecting them up to the house network. Now they were immortal, just like me, and they knew that I was their alpha dog. They loved to go for walks with me.

I spotted the wumpus by the plume of dust it kicked up. It was well inside the perimeter, gnawing at the corner of an old satellite Ford factory, a building gone to magnificent ruin, all crumbled walls and crazy, unsprung machines. The structural pillars stuck up all around it, like columns around a Greek temple.

The wumpus had the classic look. It stood about eight feet tall, with a hundred mouths on the ends of whipping tentacles. Its metallic finish was smeared with oily rainbows that wobbled as the dust swirled around it. The mouths whipped back and forth against the corner of the factory, taking chunks out of it. The chunks went into the hopper on its back and were broken up into their constituent atoms, reassembled into handy, safe, rich soil, and then ejected in a vertical plume that was visible even from several blocks away.

Wumpuses don’t put up much fight. They’re reclamation drones, not hunter-killer bots, and their main mode of attack was to assemble copies of themselves out of dead buildings faster than I could squash them. They weren’t much sport, but that was OK: there’s no way Dad would let me put his precious mecha at risk against any kind of big game. The pack loved hunting wumpus, anyway.

The air-drones swooped around it in tight arcs. They were usually piloted by Pepe, the hysterical chihuahua, who loved to have three points-of-view, it fit right in with his distracted, hyperactive approach to life. The wumpus didn’t even notice the drones until one of them came in so low that it tore through the tentacles, taking three clean off and disordering the remainder. The other air-drones did victory loops in the sky overhead, and the flea bounded so high that it practically disappeared from sight, then touched down right next to the wumpus.

This attack was characteristic of Gretl, the Irish Setter mix who thought she was a kangaroo. The whole pack liked the flea, but Gretl was born to it. She bounced the wumpus six times, knocking it back and forth like an air-hockey puck, leaping free before it could bring its tentacles to bear on her.

The ground-effect bots reached the wumpus at the same time as I did. Technically, I was supposed to hang back out of range and get it with the mecha’s big guns, to make sure that it didn’t get a bite or two in on the mecha’s skin, scratching the finish. But that was no fun at all. I liked to dance with the wumpus, especially when the pack was in on it, all of us dodging in and out, snatching the wumpus’s tentacles, kicking it back and forth. The ground-effect bots were clearly piloted by Ike and Mike, two dogs that had been so badly mutilated when I found them that I couldn’t even guess at their breed. They must have been big beasts at one point. They were born to ground-effect bots, anyway, bulling the wumpus around.

The wumpus was down to just a few tentacles now, and I could see into its hopper, normally obscured by the forest of waving arms and mouths. The hopper itself was lined with tentacles, but thin ones, whiplike, each one fringed with hairy cilia. The cilia branched and branched again, down to single-molecule pincers, each one optimized to break apart a different kind of material. I knew better than to reach inside that hopper with the mecha’s fists—even after I’d killed the wum-pus, the hopper would digest anything I fed it, including me.

Its foot-spoked wheels spun madly as we batted it around like a cat playing with a mouse. They could get traction on anything, given enough time to get their balance, but we weren’t going to give it the chance. The air-drones snipped the last of the tentacles, and I touched the control that whistled the pack back. They obediently came to my heels, and I put the wumpus in my sights. The wumpus seemed to sense what was coming. It stopped struggling and settled down on the feet of its wheels. I methodically blew apart its hopper with my depleted uranium guns, chipping away at it, blowing it open, cilia waving and spasming. Now the wumpus was just a coil of metallic skin and logic with a hundred wheels, naked and stripped. I used the rocket-launcher on it and savored the debri

s-fountain that rose from it. Sweet!

“Jimmy Yensid, you are cruel and vile!” The voice bounced off the walls of the ruined buildings around me, strident and shrill. I rotated the mecha’s cowl and scanned the ground. There she was, standing on top of a dead hover-bus, a spidergoat behind her on a tether. I popped the cowl and shinned down the mecha, using the grippy hand- and toe-holds that tried to conform to my grasp.

“Hello, Lacey!” I called. “You’re looking very pretty today.” Dad had always taught me to talk to girls this way, though there weren’t many meat girls in my world, just the ones I saw online and, of course, the intriguing women of the Carousel of Progress, back in the center of Comerica Park. And it was true. Lacey Treehugger was ever so pretty—with a face as round as a pie-plate and lips like a drawn-up bow. Talking to Lacey was as forbidden as destroying the mecha, maybe more, but Dad could tell if the mecha got scratched and he had no way of finding out if I had been passing the time of day with pretty Lacey.

She was taller than me now, which was only to be expected, because she was not immortal and so she was growing at regular speed while I was going to stick to my present, neat little size for a good while yet. I didn’t mind that she was taller, either—I liked the view.

“Hello, hello,” I said as I scaled the hover, coming up to stand next to her. “Hello!” I said to the spider-goat, holding out the flat of my hand for it to sniff. It brayed at me and menaced me with its horns. “Come on, Louisa, play nice.”

She tugged on the goat’s lead, a zizzing spool of something that felt as soft as felt but could selectively tighten at the loop-end when the goat got a little too edgy. “This isn’t Louisa, Jimmy. This is Moldavia. Louisa died last week.” She glared at me.

“I’m sorry to hear it,” I said. “She was a good goat.”

“She died from eating bad sludge,” Lacey said. Ah. Well, that explained it. Lacey’s people hated Dad’s preserve here in the old city of Detroit. They hadn’t made the wumpuses, but they fully supported their work. The Treehuggers wanted all of the old industrial world converted back to the kind of thing you could let a goat eat without worrying about it dropping dead, turning to plastic, or everting its digestive tract.

“You should keep a closer eye on your goats, Lacey,” I said. “It’s not safe for them to wander around here.”

“It would be if you’d leave off hunting those innocent wumpuses. The way you took that poor thing apart, it was sickening.”

“Lacey, it’s a machine. It doesn’t have feelings. I was just having a little fun.”

“Sickening,” she repeated. She had her short hair in tiny braids today, which is one of the many ways I loved to see it. Each braid was tipped with a tiny, glittering bead of fused soil, stuff that her people collected as a reminder of the bad old days.

“How’s your parents?”

She didn’t manage to hide her smile. “Their weirdness is terminal. This week they decided that we were going to try to sell spider-goat silk to India. I’m all like, India? Are you crazy? What does India want with our textiles? They don’t even need clothes there anymore, not since desidotis came out.” Desidotis were self-cleaning, self-replicating, and could reconfigure themselves. No one who made dollars could afford them—they were denominated in rupees only. “And they went, have you seen how the rupee is trading today? So they’re all over iBay, posting auction listings in broken Hindi. I’m all like, you know that India is the world’s largest English-speaking nation, right?”

I shook my head. “You’re right. Terminally weird.”

She gave me a playful shove. “You’re one to talk. At least mine are human!”

So technically it was true. Dad refused to call himself a human anymore. Ever since he attained immortality, decades before I was born, he’d called himself a transhuman. But when he said he wasn’t human, it was a boast. When Lacey said it, it sounded like an insult. It bugged me. Dad didn’t want me “deracinating” myself with Lacey. Lacey didn’t trust me because I wasn’t a “real” human. It wasn’t like I wanted to be a mayfly, like the Treehuggers were, but I still hated it when Lacey looked down her nose at me.

“I really do hate the way you take those wumpuses apart,” she said. “It gives me the creeps. I know they’re not alive, but you really seem to be enjoying it.”

“The pack enjoys it,” I said, gesturing at my robots, who were wrestling each other around my feet. “It’s in their nature to hunt.”

She looked away. “I don’t like them, either,” she said, barely above a whisper.

“Come on,” I said. “They’re better off now than they were when I found them. At least I haven’t screwed around with their germ plasm. I’m just using technology to let them be better dogs. Not like Louisa there.” I pointed to the spider-goat.

“Moldavia,” she said.

I knew I had her there. I pressed my advantage. “You think she enjoys giving silk? Somewhere in her head, she knows she’s supposed to be full of milk.”

Lacey looked out over the ruins of Detroit. “Pretty around here,” she said.

“Yeah,” I said. It was. The ruins were glorious. They were all I’d ever known, except for flyovers in the zepp. Michigan countryside was pastoral and picturesque, but it wasn’t anything so magnificent as Detroit’s ruins. So much ambition. Made me proud to be (trans)human. “I wish you guys would stop trying to take it away from us.”

This is how conversation with Lacey always went, each of us picking fights with the other. It was all we knew, the best way we had to relate. Neither of us really meant it. It was just an excuse to stand close enough to her to count the hairs on her arms, to watch the sun through her eyelashes.

She looked at me. “It’s not like you let anyone else come by and see it anyway. You just hoard it all to yourself.”

“You come by whenever you want. What’s the problem?”

“You treat it like your own private playground. You know how many people could live here?”

“None,” I said. “It would kill them within a week.” I was immune, thanks to my transhuman liver. Dad’s liver wasn’t quite so trick, but he made do by eating cultured yogurt filled with microbes that kept him detoxed. He said it was a small price to pay for continued residence in his museum.

“You know what I mean,” she said, socking me again. “Let the wumpuses do their thing, turn this whole place back into forests, grow some treehouses … How many? A million? Two million?”

“Sure,” I said. “Provided you didn’t care about destroying all this history.”

“There are billions of blown-out steel-belted radials!” she said. “All over the world. What the hell makes yours so special?”

“What if this was ancient Rome?” I said. “What if we were all sitting around, thinking about pounding down all those potsherds, and you were all like, Jimmius Yensidus, what are you saving all those potsherds for? Rome is full of them. They’re a health hazard! The centurions keep cutting their feet on them!”

“You are a total idiot,” she said.

We got to this point in every discussion. Half the time, I called her an idiot. Half the time it was the other way around. We sat down on the bus and she put her arm around me. I leaned in for my kiss. Dad would totally splode if he knew. Deracination!

Sorry, Dad. She kissed me slowly, with a lazy bit of tongue that made the hair on my neck stand up. She was probably getting a little old for me, but I found that I quite liked older women.

She broke it off and sighed. “You’re so young,” she said. “We can’t keep doing this.”

“I’m two months older than you,” I said, baiting her. I knew what she meant.

“You used to be. These days, it’s like you’re ten. I’m almost fourteen, Jimmy.”

“So go kiss some Treehugger boys on the spider-goat farm,” I said.

She sighed again. “Are you really happy here?”

“Are you happy where you are?”

“I’m happy enough. It’s peaceful

.”

“Boring.”

“Yeah,” she said.

“It’s not boring around here. Going out with Dad is awesome.” Dad collected pieces for his museum from all over the world. We’d gone to France together the year before to get the Girl and the Sultan’s Elephant from Marseilles. The semirobotic puppets were eleven meters tall and we’d stashed them in a high-school gym near the bus station. We couldn’t work them on our own, they needed a crew of twenty or more, but I was working on training the pack to help out. Trying, anyway. Pepe kept trying to eat the Elephant.

“But you’re all alone. And your dad is so weird.”

“He’s weird, but he’s a lot of fun. I won’t live here forever, anyway. Once I’m post-pube, I’m going on a vision-quest. It’s part of the package. Then I’ll find somewhere to settle down.”

“You’ve got it all figured out, huh?”

Pepe had been circling high overhead as we chatted, occasionally dipping down to play with the ground-effect critters. Now all three of his drones lofted high, making wide circles. That was the signal that he was seriously freaking out.

I stood up to get a better look at him, Lacey grabbing at my hand. I followed the wide, swooping curves of the drones, turning to watch, and saw two of them get shot out of the sky, one-two, just like that, disappearing in a hail of debris.

Lacey squeezed my hand.

“Kurzweil on a crutch,” I breathed. I headed for the mecha, but Lacey wouldn’t let go of my hand. “Come on,” I said, looking into her scared face. “You ride shotgun, I’ll get you home safe.” She shook her head. Her eyes were white. The pack was going crazy around us, nipping at our heels, racing in circles. The flea was springing high, high, higher. The crack of artillery. A flight of rockets screamed overhead, then touched down somewhere. The sound was incredible, like nothing I’d ever heard, and the earth shook so hard that I slipped and went down on one knee.

“Come on,” I said to Lacey, “get in!”

I grabbed for the bottom rung of the mecha’s handholds and felt it grip me back. I looked over my shoulder. Lacey was hugging the goat. Dammit. The goat.

Pirate Cinema

Pirate Cinema Walkaway

Walkaway Little Brother

Little Brother Someone Comes to Town, Someone Leaves Town

Someone Comes to Town, Someone Leaves Town The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow

The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow Super Man and the Bug Out

Super Man and the Bug Out For the Win

For the Win A Place so Foreign

A Place so Foreign Shadow of the Mothaship

Shadow of the Mothaship Return to Pleasure Island

Return to Pleasure Island Party Discipline

Party Discipline Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom

Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom Lawful Interception

Lawful Interception Homeland

Homeland Eastern Standard Tribe

Eastern Standard Tribe Chicken Little

Chicken Little I, Row-Boat

I, Row-Boat Makers

Makers Rapture of the Nerds

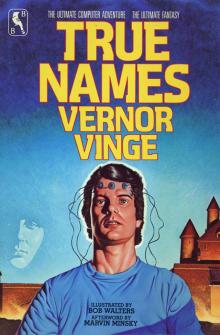

Rapture of the Nerds True Names

True Names