- Home

- Cory Doctorow

The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow Page 6

The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow Read online

Page 6

“I’m just saying it’s not as good as you think it is.”

“You get to have sex!” I blurted. “You get to know what it’s like.”

“You’ve never?”

“Never,” I said. “Physiologically, I’m eleven or twelve. No adult would have sex with me. And it’s not right for me to make out with little kids. The last girl I kissed was you, Lacey.”

“Oh, Jimmy,” she said. She stroked my hair. “I’m sorry. It’s hard to know how to think of you. Sometimes I think you’re just a little kid, but you’re actually a little older than me, aren’t you?”

“Yeah,” I said. “But my brain doesn’t age much either. It’s too plastic. I don’t get to build up layers of experience one on top of another—it slips out underneath. I really have to concentrate to think properly. The local scientists would be freaked out about this if they could be freaked out about anything. This is probably the only place in the world where never changing is considered to be a signal virtue.”

I realized that I was balling up my fists and so I relaxed them and took some deep breaths. Lacey was snuggled up against me and it was warm and good. I tried to focus on that, and not the yawning pit in my gut.

“You’re not going to take me with you, are you?”

She swallowed. “We’ll see.”

I knew what that meant.

I tried not to let her hear me cry, but it shook my ribs, and she hugged me harder. She didn’t say, “I’ll take you with,” though. Of course not. She didn’t want to have a kid, an instant son.

I woke from a strange dream of kissing and sliding skin. I had a rock hard erection, like nothing I’d ever felt before. There was that itch again, in my belly, that I supposed meant “horny,” though I’d never felt it like this. Lacey had drooped away from me in her sleep and was lying on her back beside me. In the dim light of the pack’s glowing power-indicators, I could see her chest rising and falling, her nipples visible through the thin fabric of her nightshirt. I remembered what she’d looked like naked the other night. She must have noticed my reaction, because she’d changed in private every night since. I realized that that was what I’d been dreaming of.

I reached out with a tentative hand and let it barely graze over her breast. She didn’t stir. It felt soft, giving under my finger. My mouth was bone dry. I pulled back the coverlet. Her long t-shirt had ridden up, and I could see her legs all the way up to the curve of her hip. I touched her hip, stroking it with the same hesitancy. Warm. Jouncy—firm but giving. I touched her thigh. She muttered something and stirred.

I froze. She put one hand on her tummy, and her shirt rucked up higher. Now I could see all her hair down there. It was too dark to see anything more. I put my hand on her thigh again, halfway up. Her breathing didn’t change. I slid my hand higher. Higher still.

My smallest finger brushed up against something very soft and a little moist, something that felt like a warm mushroom.

“Jimmy?”

I knew that she was awake, fully awake. I snatched my hand away.

“God, I’m sorry Lacey.”

“What are you doing, Jimmy?”

“I—” I couldn’t find the words. It was too embarrassing, too weird. Too creepy.

“It was the sex talk, huh?”

I swallowed. I calmed myself down. I decided I could talk about this like a man of science. “I’m not quite physiologically there, when it comes to sex. I’m sort of stuck between the first stage of sexual maturity and childhood. Normally, it’s not a problem, but …” I ran out of science.

“Yeah,” she said. “I wondered about that. Come here, Jimmy.”

Awkwardly, I snuggled up to her, letting her spoon behind me.

“No,” she said. “Turn around.”

I turned around. I had my little boner again, and I was conscious of how it must be pressing against her thigh, the way her breasts were pressed against my chest. Her face was inches from mine, her breath warm on my lips.

She kissed me.

She kissed exactly like I remembered it, twenty years before. Slowly, with a lazy bit of tongue. Her teeth were warm in her mouth as I tentatively reciprocated. She took my hand and put it on her breast. Her nipple was a little bump in the center of my palm, the flesh of her breast yielding under my hand. I squeezed it and rubbed it and touched it, almost forgetting the kiss. She laughed a little and pulled her shirt up and pulled my face down to her breasts. I kissed them, kissed the nipples, unsure of what to do but hearing her breath catch when I did something right. I tried to do more of that. It was fascinating. The pack roused itself and squirmed over us. I pushed them away.

She gave a soft little moan. Her hands roamed over my back, squeezed my butt. Her hand found my little boner. I gave a jolt, then another as she started to move her hand. Then I felt something like a sneeze, that started in my stomach and went down. There was sticky stuff on her hand.

“Wow,” I said. “I didn’t know I could do that.”

“Let’s find out what else you can do,” she said.

The next day was my scheduled day at the research station, but I didn’t want to leave Lacey alone in the Carousel, not now that Sebastien and Tina knew about her. They might come by to ask her some questions about her intentions.

Besides, there was the matter of what we’d done the night before. It had lasted for a long time. There was a lot I didn’t know. When we were done, I knew a lot more. And it was all I could think of, from the moment I woke up with the smells on me and the small aches here and there; while I was in the bathroom and pissing through a dick that felt different, gummy and sticky; while I was washing up and digging some grapefruits out of my storehouse for breakfast, slicing them open and grabbing water from the osmotic filter for the day.

Lacey was sitting up in bed, the pack arrayed around her, the sheet not covering her beautiful breasts. Her hair was in great disarray and her mouth was a little puffy and swollen from kissing.

“Good morning,” she said, and smiled at me, her little bow mouth widening into a giant grin.

I smiled back and handed her a grapefruit. I cuddled up to her as we ate and she laughed when I got a squirt of grapefruit in the eye. We didn’t say much, but then the Flea, who is also in charge of my calendar reminders, began to chitter at me to tell me it was time to go to the lab.

“What’s he want?”

“I’m supposed to see the researchers here. About my immortality. I go every couple of weeks and they do more tests, measure me. Whatever Dad did to my germline wasn’t documented anywhere public. He had all these buddies around the world who had treated themselves to make them immortal, and they were all refining the process. None of them seem to be anywhere that we can find them, so we’re trying to reverse-engineer them.”

“What kind of researchers would a place like this have? I’d have thought that they would be pretty hostile to R&D in a place that isn’t supposed to change.”

“Well, when the whole world is changing all the time, it takes a lot of R&D to respond to it so that you don’t change along with it. Some of them are pretty good. I looked up their bios. They were highly respected before they became wireheads. Mellowing out your emotions shouldn’t interfere with your science anyway.”

“Are they trying to cure your immortality or replicate it?”

I turned to look at her. “What do you mean? Cure it, of course.”

“Really? If they don’t want any change, wouldn’t it make sense to infect everyone with it?”

“It makes a perverse kind of sense, I suppose. If you were into conspiracy theories, it would be believable. But I know these guys—they don’t have it in them to lie to me, or to make me sad on purpose. That’s the good thing about living here: you can always be sure that the people around you are every bit as nice as they seem. Sincere.”

“If you say so,” she said. Even though she didn’t have an antenna, I could feel her skepticism. Fine, be skeptical. Wireheads didn’t scheme, they just did stuff, t

hat was what it meant to be a wirehead. She nuzzled my neck. I turned my head and we kissed. It was weird with the lights on.

I broke it off and said, “I’ve got to get to the lab.” The Flea was running in little circles and chiding me, making the point. I pulled on my jumpsuit and zipped it up.

“Will you be long?”

I shrugged. “Couple hours,” I said. “Don’t answer the door, OK? I mean, just lay low. Stay here. My neighbors—”

“I get it,” she said. “Don’t want to get kidnapped and wired up, right?”

“They won’t kidnap you. Just put the question to you and kick you out if you give the wrong answer.”

She opened her arms. “Come give me a kiss goodbye, my brave protector,” she said. I leaned in and let her give me a hard hug and a harder kiss. The hug felt like that first night, when it was just the chance to have a human being holding me; the kiss felt like the night before, when we’d done things I’d never given much thought to.

“Love you, Jimmy,” she whispered fiercely in my ear.

Dad used to say that a lot. “You too,” I said, because it was what I always said to him.

The sun was high and the day was crisp, the kind of weather that made you forget just how hot it could be in the summer. Drifts of colored leaves rustled around me as the bare trees sighed in the wind. The sun was bright and harsh. I’d been through many of these autumns, but I’d never had a day that felt this autumnal, this crisp and real and vivid.

There were plenty of wireheads out and about. Some of them were driving transports filled with staple crops grown in our fields. Some were chatting with traders, who blew through town every day. Some were just sitting on a bench and smiling and nodding at the passers-by, which might as well be the cult’s national sport.

They greeted me, one and all. Everyone knew me and no one asked me nosy questions about my … condition. Everyone knew enough to know that I was just the kid who wouldn’t grow up, and that I could give them a fine show if they came and knocked on my door.

Normally that felt good. Today, it loomed over me, oppressing me. They’d all have heard about Lacey by now. They were seeing me walk down the street, so they knew that Lacey must be alone in the Carousel. They’d be thinking together, wondering about her, thinking about going over there to find out when she’d be signing up for her wire. And that was the one thing I didn’t want. Lacey had managed to change over the past twenty years, becoming an adult, leaving behind Treehuggerism, having adventures. Turning into a woman. I didn’t want her frozen in time the way we all were. I didn’t want to be frozen in time anymore. Besides, she knew my secret now, that my antenna didn’t work the way everyone else’s did. If she became a wirehead, she’d tell them about it. She’d have to.

The labs had been in the old University bioscience building, but a trader had sold the researchers a self-assembling lab-template a couple years before. The wireheads had held a long congress about putting up a major building, but in the end, the researchers were made so clearly miserable by the prospect of not being able to put up a new building that they’d prevailed; the wireheads had caved in just to get them to cheer the hell up.

The new building looked like a giant heap of gelatinous frogspawn: huge, irregular bubbles in a jumble that spread wide and high. The template had taken in the disciplinary needs of the researchers and analyzed their communications patterns to come up with an optimal geometry for clustering research across disciplines and collaborative groupings. The researchers loved it—you could feel that just by getting close to the build-ing—but no one else could make any sense of it, especially since the bubbles moved themselves around all the time as they sought new, higher levels of optimal configuration.

I could usually find my research group without much trouble. I climbed up a few short staircases, navigated around some larger labs filled with equipment that Dad would have loved, and eventually arrived at their door. There were three of them today: Randy, the geneticist; Inga, the endocrinologist; and Wen, the oncologist.

“You think it’s cancer again, huh?”

Randy and Inga nodded gravely at Wen. “That’s our best guess, Jimmy. It’s the cheapest and easiest way to get cells to keep on copying themselves. We thought we’d try you out on some new anticancer from India.” Inga was in her thirties; I’d played with her when she was my age. Now she seemed to see me as nothing more than a research subject.

Wen nodded and spread his hands out on the table. “We infiltrate your marrow with computational agents that do continuous realtime evaluation of your transcription activity, looking for anomalies, comparing the data-set to baseline subjects. Once we have a good statistical picture of what’s happening, we intervene in anomalous transcriptions, correcting them. It’s a simple approach, just brute force computation, but there’s a new IIT nanoscale petaflop agent that raises the bar on what ‘brute force’ really means.”

“And this works?”

They all looked at each other. I felt their discomfort distantly in my antenna. “It’s had very successful animal trials.”

“How about human trials?” I already knew the answer.

“Dr Chandrasekhar at IIT has asked us to serve as a test site for his human trials research. He was very impressed with your germ plasm. He’s been culturing it for months.” Randy was getting his geek back, a pure joy I could feel even through my muffled receiver. “You should see the stuff he’s done with it. Your father—”

“A genius, I know.” I didn’t usually mind talking about Dad, but that day it felt wrong. I’d pictured him once, briefly, as Lacey and I had been together, and had zigged wrong and ended up bending myself at an awkward angle. It was the thought of what Dad would say ifhe caught me “deracinating.”

“He didn’t keep notes?”

“Not where I could get at them. He had a lot of friends around the world—they all worked on it. There’s probably lots more like me, somewhere or other. He told me he’d let me in once I was old enough.”

“Probably worried about being generation-gapped,” Randy said sagely.

“I don’t get it,” I said.

“You know. Whatever he’d done to himself, you were decades further down the line. If he’d kept up what he was doing, and if you’d joined him, you’d have been able to do it again, make a kid who was way more advanced than you. You’d end up living forever like a caveman among your genius superman descendants. So he wanted to keep the information from you.” He shrugged. “That’s what Chandrasekhar says, anyway. He’s done a lot of research on immortality cabals. He didn’t know about your dad’s, though. He was very impressed.”

“So you said.” I hadn’t really thought about this before. Dad was—Dad. He was all-seeing, all-knowing, all-powerful. He hadn’t just fathered me, he’d designed me. Of course, he’d designed me to patch all the bugs in his own genome, but—

“So as I said, we’ve cultured a lot of your plasm and run this on it. What we get looks like normal aging. Mitochondrial shortening. Maturity.”

“How big a culture?” I was raised by a gifted bioscien-tist. I knew which questions to ask.

“Several billion cells,” Inga said, with a toss of her hair. I could feel their discomfort again, worse than before.

“Right …” I did some mental arithmetic. “So, like, a ten-centimeter square of skin?”

The three of them grinned identical, sheepish grins. “It scales,” Inga said. “There’s a four-hundred-kilo gorilla running it right now. Stable for a year. Rock solid.”

I shook my head. “I don’t think so,” I said. “I mean, it’s very exciting and all, but I’ve already been a guinea pig once, when I was born. Let someone else go first this time.”

They all looked at each other. I felt the dull throb of their anxiety. They looked at me.

“We’ve been looking for someone else to trial this on, but there’s no one else with your special—” Wen groped for the word.

“There has to be,” I said. “Dad d

idn’t invent me on his own. There was a whole team of them. They all wanted to make their contributions. There’s probably whole cities full of immortal adolescents out there somewhere.”

“If we could find them, we’d ask them. But no one we know has heard of them. Chandrasekhar has put the word out everywhere. He swings a big stick. He said to ask if you know where your dad’s friends lived?”

“Dad had a huge fight with those people when I was born, some kind of schism. I never saw him communicating with them.”

“And your mother?”

“Dead. I told you. When I was an infant. Don’t remember her, either.” I swallowed and got my temper under control. Someday, someone was going to notice that even when I looked all pissed off, my antenna wasn’t broadcasting anything and I’d be in for it. They’d probably split me open and stick five more in me. Or tie me naked to a tree and leave me there as punishment for deceiving them. It’s amazing how cruel you can be when there’s a whole city full of people who’ll soak up your conscience and smooth it out for you.

“Chandrasekhar says—”

“I’m getting a little tired of hearing about him. What is it? Is it ego? You want to impress this big-shot doctor from the civilized east, prove to him that we’re not just a bunch of bumpkins here? We are a bunch of bumpkins here, guys. We live in the woods! That’s the point. What do you think they’d all say if they knew you were trying this?” I waved my arm in an expansive gesture, taking in the whole town. I knew what it was like to have a dirty little secret around there, and I knew I’d get them with that.

Inga’s face clouded over. “Listen to me, Jimmy. You started this. You came to us and asked us to investigate this. To cure you. It’s not our fault that answering your question took us to places you never anticipated. We’re busy people. There are plenty of other things we could be doing. We all have to do our part.”

The other two were flinching away from the sear of her emotion. I did what any wirehead would do when confronted with such a blast: I left.

Pirate Cinema

Pirate Cinema Walkaway

Walkaway Little Brother

Little Brother Someone Comes to Town, Someone Leaves Town

Someone Comes to Town, Someone Leaves Town The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow

The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow Super Man and the Bug Out

Super Man and the Bug Out For the Win

For the Win A Place so Foreign

A Place so Foreign Shadow of the Mothaship

Shadow of the Mothaship Return to Pleasure Island

Return to Pleasure Island Party Discipline

Party Discipline Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom

Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom Lawful Interception

Lawful Interception Homeland

Homeland Eastern Standard Tribe

Eastern Standard Tribe Chicken Little

Chicken Little I, Row-Boat

I, Row-Boat Makers

Makers Rapture of the Nerds

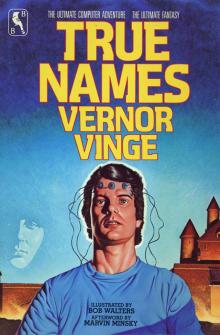

Rapture of the Nerds True Names

True Names