- Home

- Cory Doctorow

The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow Page 8

The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow Read online

Page 8

“You know that there’s been a woman staying with me?”

She made a face. “It’s not any of my business, and I don’t really have any romantic advice—”

I cut her off. I told her everything. Even the sex parts. Even the antenna parts. Especially the wumpus parts. For such a big load of secrets, it didn’t take long to impart.

“So you think she’ll attack the city?”

I suppressed my own irritation—maybe it was the dull reflection of hers. “I know she will.” I took out my console and showed her the pictures of the wumpus.

“So you’re telling me this. Why? Why not wake up someone important? Someone who can help us?”

“I don’t think there’s any helping us. You saw it. You saw its babies. It’s coming for us, soon. This place is all over. I don’t know if it eats people, but it’s going to eat everything human-made here. That’s what they do.”

I felt her draw strength and calm from the sleeping people around us, from the whole city, dissipating her fear through the network.

“So why are you here?”

“I want you to give me the Chandrasekhar treatment before I go.”

“You’re leaving?”

I gestured at my wagon.

“And you want the cure? Yesterday you didn’t want to be a guinea pig.”

“Yesterday I thought there’d be a tomorrow. Now I’m not so sure. I want the cure.”

She folded her arms and stared at me.

“Your antenna isn’t totally dead, you know,” she said at last. “I can sort of feel a little of what you’re feeling. It’s too bad it doesn’t work better. That’s not a good way to feel.”

“You’ll do it?”

“Why not? It’s the end of the world, apparently.”

The sound of frying bacon filled the night as we worked in her lab. We dilated the windows at first, so we could track the progress of the wumpuses through town. There were a lot of angry shouts and sobs, but nothing that sounded like screams of pain. The wumpuses were apparently eating the buildings and leaving the people, just as they had two decades before.

The procedure was surprisingly simple—mostly it was just installing some code on my console and then a couple of shots from a long, thin bone-needle. That hurt, but less than I expected. I made sure I had the source-code as well as the object-code in case I needed to debug anything: the last thing I wanted was to be unable to manage my system.

We watched in fascination as statistical data about my transcriptions began to fill the screens around us. The app came with some statistically normal data-sets that overlaid the visualizations of my own internal functionality. It was clear even to my eye that I was pretty goddamned weird down there at the cellular level.

“What happens now?”

“The thing wants a full two month’s worth of data before it starts doing anything. So basically, you run that for a couple of months, and then it should prompt you for permission to intervene in your transcriptions to make them more normal.”

“Two months? That must suck if you’ve got cancer.”

“Cancer might kill you in two months and it might not. Bad nanites messing with your cellular activity is a lot scarier.”

“I’ve been trying not to think of that,” I said.

The frying bacon noises were growing louder.

“No more shouts,” Inga said. Her eyes were big and round. “What do you think is going on out there?”

I shook my head. “I’m an idiot, give me a second.”

I gathered the pack in my arms and gave them their instructions, then tossed them out the window. They scampered down the building side and I fired up the console.

“There,” I said, pointing. The wumpuses were moving in a long curved line now, a line as wide as the town, curving up like a pincer at the edges. They moved slowly and deliberately through the night. Pepe found a spot where they were working their way through a block of flats, tentacles whipping back and forth, great plumes of soil arcing out behind them. People ran out of the house, carrying their belongings, shouting at the wumpuses, throwing rocks at them. The wumpuses took no notice, save to snatch the thrown rocks out of the air and drop them into their hoppers.

An older man—I recognized him as Emmanuel, one of the real village elders around here—moved around to confront the wumpus that was eating his house. He shouted more words at it, then took another step toward it.

One of the tentacles moved faster than I’d ever seen a wumpus go. It whipped forward and snatched Emmanuel up by the torso and lifted him high in the air. Before he could make a sound, it had plunged him headfirst into its hopper. One of his legs kicked out, just once, before he disappeared.

The other wireheads around him were catching the fear, spread by the wires, too intense to damp down. They screamed and ran and the wumpuses picked them up, one after another, seeming to blindly triangulate on the sounds of their voices. Each one went headfirst into the hopper. Each one vanished.

I stood up and whistled the pack back to me.

I moved for the door. Inga blocked my way.

“Where are you going?”

“Away,” I said. I thought for a moment. “You can come if you want.”

She looked at me and I realized that what I’d always mistaken for pity was really a kind of disgust. Why not? I was the neighbor kid who’d never grown up. It was disgusting.

“You brought her here,” she said, quietly. I wondered from the tone of her voice if she meant to kill me, even though she’d just treated me.

“She came here,” I said. “I had nothing to do with it. Just a coincidence. Sit in one place for twenty years and everyone you’ve ever known will cross your path. Whatever she’s doing, it’s nothing to do with me. I explained that.”

Inga slumped into a lab-chair.

“Are you coming?” I asked.

She cried. I’d never heard a wirehead cry. Either there wasn’t enough mass in the wirehead network to absorb her emotion or the prevailing mood was complete despair. I stood on the threshold, holding my wagon filled with the pack’s canisters. I reached out and grabbed her hand and tugged at it. She jerked it away. I tried again and she got off her stool and stalked deeper into labs.

That settled it.

I left, pulling my wagon behind me.

The sound of frying bacon was everywhere. I had the pack running surveillance patterns around me, scouting in all directions, their little squirrel cases eminently suited to this kind of thing. We were a team, my pack and me. We could keep it up for days before their batteries needed recharging. I’d topped up the nutrients in their canisters before leaving the Carousel.

The frying bacon sound had to include the destruction of the Carousel. Every carefully turned replacement part, all those lines of code. The mom and the dad and the son and the sister and the grandparents and their doggies. Dad’s most precious prize, gone to wumpusdust.

The sound of frying bacon was all around us. The sound of screams. Lacey had arrived from the west. To the east was the ocean. I would go south, where it was warm and where, if the world was coming to an end, I would at least not freeze to death.

There was a column of refugees on the southbound roadway, the old Route 40. I steered clear of them and crashed through the woods instead, the wagon’s big tires and suspension no match for the uneven ground, so that I hardly moved at all.

The pack raced ahead and behind me, playing lookout. They were excited, scared. I could still hear the screams. Sometimes a wirehead would plunge past me in the night, charging through the woods.

The wumpus came on me without warning. It was small, small enough to have nuzzled through the trees without knocking them aside. Maybe as tall as me, not counting those whiplike tentacles, not counting the mouths on the end of them, mouths that opened and shut against the moonlight sky in silhouette.

I remembered all those wumpuses I’d killed one tentacle at a time. These wumpuses seemed a lot smarter than the ones I’d known

in Detroit. Someone must have kludged them up. I wondered if they knew how I’d played with their ancestors. I wondered if Lacey had told them.

Wumpuses only have rudimentary vision. Their keenest sense is chemical, an ability to follow concentration gradients of inorganic matter, mindlessly groping their way to food sources. They have excellent hearing, as well. I stood still and concentrated on not smelling inorganic.

The wumpus’s tentacles danced in the sky over me. Then moving as one, the pack leapt for them.

The pack’s squirrel bodies looked harmless and cute, but they had retractable claws that could go through concrete, and teeth that could tear your throat out. The basic model was used for antipersonnel military defense.

The wumpus recoiled from the attack and its tentacles flailed at the angry little doggies that were mixed among its roots, trying to pick them off even as they uprooted tentacle after tentacle.

I cheered silently and pulled the wagon away as fast as I could. I looked over my shoulder in time to see one of my doggies get caught up in a mouth and tossed into the hopper, vanishing into a plume of dust. That was OK—I could get them new bodies, provided that I could just get their canisters away with me.

I tugged the wagon, feeling like my arm would come off, feeling like my heart would burst my chest. I had superhuman strength and endurance, but it wasn’t infinite.

In the end, I was running blind, sweat soaking my clothes, eyes down on the trail ahead of me, moving in any direction that took me away from the frying bacon sound.

Then, in an instant, the wagon was wrenched out of my hand. I grabbed for it with my stiff arm, turning around, stumbling. There was another wumpus there, holding the wagon aloft in two of its mouths. The canisters tumbled free, bouncing on the forest floor. The wumpus caught three of them on the first bounce, triangulating on the sound. I watched helplessly as it tossed my brave, immortal, friends into its hopper, digesting them.

Then the fourth canister rolled away and I chased after it, snatching at it, but my fingertips missed it. A hand reached out of the dark and snatched it up. I followed the hand back into the shadows.

“Oh, Jimmy,” Lacey said.

I leapt for her, fingers outstretched, going for the throat.

She sidestepped, tripped me with one neat outstretched foot, then lifted me to my feet by my collar. I grabbed for the canister, the last of my friends, and she casually flipped it into the wumpus’s hopper.

A spray of dust coated us. The plume. My friend.

I began to cry.

“Jimmy,” she said, barely loud enough to be heard over the frying bacon. “You don’t understand, Jimmy. They’re safe now. It’s copying them. Copying everything. That’s what we never understood about the wumpuses. They’re making copies of the things that they eat.”

She set me down and grabbed me by the shoulders. “It’s OK, Jimmy. Your friends are safe now, forever. They can never die now. The wireheads, too.”

I stared into her eyes. I’d loved her. She was quite mad.

“What do you get out of it?”

“What did your father get out of what he did? He made one child immortal. We’ll save the world. The whole world.” She smiled at me, like she expected me to smile back. I smiled back and she relaxed her grip on my arms. That’s when I clapped her ears, cupping my hands like I’d been taught to do if I wanted to rupture her eardrums. Dad liked to work through self-defense videos with me.

She went down with a shout and I stepped on her stomach as I clambered over her and ran, ran, ran.

PART 3: THERE’LL ALWAYS BE THE GOOD GUYS SHOOTIN’ IT OUT WITH THE BAD GUYS

I USED TO DRIVE MECHAS for joyriding. Now it’s a medical necessity.

I piloted my suit down the Keys, going amphibious and sinking to the ocean-bottom rather than risk the bridges. The bridges were where the youth gangs hung out, eyes luminous and hard. You never knew when they’d swarm you and mindrape you.

I hated the little bastards.

The Second Wumpus Devastation had destroyed—or preserved, if you preferred—every hominid in the Keys, and taken down every human-made structure. Today, we survivors lived in treehouses and ate breadberries.

Looking at old maps, I can see that my treehouse is right in the middle of the site of the old KOA Campground on Sugarloaf key. I like it for the proximity to Haiti, where an aggressive military culture kept the island wumpus-free and hence in possession of several generations of functional mechas. There were a few years there, after I escaped from the wireheads and the wumpuses, when I grew into a strapping buck and was able to earn one of these lethal little bastards by serving in an antiwumpus militia.

“Earn” is probably the wrong word. The youth gangs wiped out the militias a few years into my stint. You’d be out on patrol and then a group of these kids would glide out of the bush so silent it was like they were on rails. They’d surround you, hypnotizing you with those eyes of theirs, with those antennae of theirs, and you’d be frozen like a mouse pinned by a cobra’s gaze. They’d SQUID you right through your armor, dropping the superconducting quantum field around your head, ripping through your life, your deep structures, your secrets and habits, making a record for the cloud, or wherever it was all the data went to.

After a thorough mindraping, hard militiamen would be reduced to shell-shocked existential whiners, useless for combat. They’d abandon their powered suits and wander off into the bush, end up in some taproom, drinking to forget the void they faced as their brains were spooled out like an archival tape being transferred to modern media.

I’d been caught out one day, the air-conditioner wheezing to keep my naked flesh cool in the form-fitting cradle of the mecha. The mecha was only twice as tall as me, practically child-sized compared to the big ones we’d had in Detroit, and it was cranky and balky. I could pick up an egg with Dad’s mecha and not break the shell. The force-feedback manipulators in this actually clicked through a series of defined settings, click-click-click, the mecha’s hands opening and closing in a clittery clatter like a puppet’s.

I waded through the swampy bush, navigating by the wumpusplume on the horizon. Somewhere, a couple clicks away, something was converting one of Florida’s precious remaining human-made structures into soil—and taking the humans along with it. No one knew if the wumpuses and the youth gangs were on the same side. No one knew if there were “sides.” The first gen of wumpuses had been made by a half-dozen agrarian cultists on the west coast. They’d been modded and hacked by any number of tinkerers who’d captured them, decompiled them, and improved them. I hear that the first could generations actually came with source-code and a makefile, which must have been handy.

They stepped out of the brush in unison. It took an eyeblink. They were utterly silent. And a little familiar.

They were me. Me, during that long, long pre-adolescence, when I was ageless and lived among the wireheads.

Oh, not exactly. There were minor variations in their facial features. Some wore their hair long and shaggy. Others kept it short. One had freckles. One was black. Two might have been Latino.

But they were also me. They looked like brothers to one another, and they looked like my own brothers. I can’t explain it better than that: I knew they were me the same way I knew that the guy I saw in my shaving mirror was me.

They surrounded my mecha in a rough circle and closed in on me. They looked at me and I looked at them, rotating my mecha’s cockpit through a full 360. I’d always assumed that they came out of a lab somewhere, like the wumpuses. But up close, you could see that they’d been dressed at some point: some had been dressed in precious designer kids’ clothes, others in hand-me-down rags. Some bore the vestiges of early allegiance to one subculture or another: implanted fashion-lumps that ridged their faces and arms, glittering bits of metal and glass sunk into their flesh and bones. These young men hadn’t been hatched: they’d been born, raised, and infected.

They made eye contact without flinching. I fought a bizar

re urge to wave at them, to get out of the mecha and talk to them. It was that recognition.

Then they raised their hands in unison and I knew that the mindrape was coming. I braced against it. The fields apparently came from implanted generators. They had the stubs of directional antennae visible behind their left ears, just as the stories said. I felt a buzzing, angry feeling, emanating from the vestiges of my wirehead antenna, like a toothache throughout my whole head.

I waited for it to intensify. I didn’t think I could move. I tried. My hand twitched a little, but not enough to reach my triggers. I don’t know if I could have killed them anyway.

The rape would come, I knew it. And I was helpless against it. I struggled with my own body, but all I could accomplish was the barest flick of an eye, the tiniest movement of a fingertip.

Then they broke off. My arm shot forward to my controls, my knuckles mashing painfully into the metal over the buttons. An inch lower and I would have mown them down where they stood. Maybe it would have killed them.

They backed away slowly, moving back into the woods. If I had been mindraped, it had been painless and nearly instantaneous, nothing like the descriptions I’d heard.

I watched the gang member directly ahead of me melt back into the brush, and I put the mecha’s tracers on him, stuck it on autopilot, and braced myself. These mechas used millimeter-wave radar and satellite photos to map their surroundings and they’d chase anything you told them to, climbing trees, leaping obstacles. They weren’t gentle about it, either: the phrase “stealthy mecha” doesn’t exist in any human language. It thundered through the marshy woods, splashing and crashing and leaping as I jostled in my cocoon and focused on keeping my lunch down.

The kid was fast and seemed to have an intuitive grasp of how to fake out the mecha’s algorithms. He used the water to his great advantage, stepping on slippery logs over bog-holes that my mecha stepped into a second later, mired in stinky, sticky mud. Once I got close enough to him to see the grime on the back of his neck and count the mosquito bites on his cheek, but then he slipped away, darting into a burrow hole as my mecha’s fingers clicked behind him.

Pirate Cinema

Pirate Cinema Walkaway

Walkaway Little Brother

Little Brother Someone Comes to Town, Someone Leaves Town

Someone Comes to Town, Someone Leaves Town The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow

The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow Super Man and the Bug Out

Super Man and the Bug Out For the Win

For the Win A Place so Foreign

A Place so Foreign Shadow of the Mothaship

Shadow of the Mothaship Return to Pleasure Island

Return to Pleasure Island Party Discipline

Party Discipline Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom

Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom Lawful Interception

Lawful Interception Homeland

Homeland Eastern Standard Tribe

Eastern Standard Tribe Chicken Little

Chicken Little I, Row-Boat

I, Row-Boat Makers

Makers Rapture of the Nerds

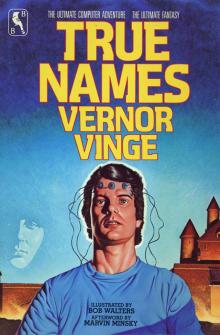

Rapture of the Nerds True Names

True Names