- Home

- Cory Doctorow

Party Discipline

Party Discipline Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

About the Author

Copyright Page

Thank you for buying this

Tom Doherty Associates ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied so that you can enjoy reading it on your personal devices. This e-book is for your personal use only. You may not print or post this e-book, or make this e-book publicly available in any way. You may not copy, reproduce, or upload this e-book, other than to read it on one of your personal devices.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

I don’t remember how we decided exactly to throw a Communist party. It had been a running joke all through senior year, whenever the obvious divisions between the semi-zottas and the rest of us came too close to the surface at Burbank High: “Have fun at Stanford, come drink with us at the Communist parties when you’re back on break.”

The semi-zottas were mostly white, with some Asians—not the brown kind—for spice. The non-zottas were brown and black, and we were on our way out. Out of Burbank High, out of Burbank, too. Our parents had lucked into lottery tickets, buying houses in Burbank back when they were only ridiculously expensive. Now they were crazy. We’d be the last generation of brown kids to go to Burbank High because the instant we graduated, our parents were going to sell and use the money to go somewhere cheaper, and the leftovers would let us all take a couple of mid-range MOOCs from a Big Ten university to round out our community college distance-ed degrees.

It was nearly time for finals, May, and it was hot, over a hundred degrees every day, and we were all a little crazy. There were the Romeos and Juliets who were feeling the impending tragedy of their inevitable breakup, the kids who knew they weren’t cut out for university or couldn’t afford it, who had no clue what they would do next, the ones who had kept their nose to their screens for four years, busting their humps to get top marks, and were just now realizing that none of it mattered for shit, and there was me.

I liked to hang out with my bestie Shirelle in the back of the portables by the old basketball court, where there was a gap in the CCTV coverage that the school filled with intermittent drone flybys. It was where the vaper kids hung out, but I wasn’t one of them. Even decaf crack wasn’t my idea of a good time. I just liked to be a little off the grid, because your business is your business, you know?

“My cousin got laid off.” Shirelle’s smart fingernails were infected with ransomware again, refusing to work on payment touchpoints and blinking in seizure-time. She was awkwardly trying to patch them, pressing each one’s hard reset while tapping her phone to it, but it was a job that really needed a third hand and since I’d told her that this was going to happen, I refused to help. So she was sitting against the portable wall with her knees drawn up and her phone balanced on them.

“Mikael?”

“No, Antoine. The sheet-metal guy.” It had been decades since Lockheed-Martin left Burbank, but there were plenty of remnants of its glory days, including all the metal-shops that had supplied it. Antoine had worked at three or four of these, hopping around as they got shut down, then he’d got a job in Encino that meant a long commute but was supposed to be a steady check.

“That job seemed too good to be true.”

“Turns out that they had a five-year tax holiday from Encino and it ran out this year. If Antoine had been smart enough to look it up, he’d have known that they weren’t going to last past July.” She got one fingernail done, moved on to the next one.

“What’s happened to the factory?”

She got another fingernail done, then dropped her phone. “Fuckydarn.”

I kicked it back to her.

“Thanks. I think”—she wedged the phone again and tried to reset her third nail—“that they’re doing an up-and-out.”

That was when a company’s tax incentives ran out and then the company ran out, too, shutting down an arm’s-length subsidiary through a fast bankruptcy and leaving its creditors—the people who worked there, say—to sort out the sale of its assets. Up-and-outs made sense because companies were hollow, they leased everything and contracted everything out. The leasing companies didn’t beef because they had a sweet loophole: they could take a write-off on the equipment that was based on the full replacement value, despite having already taken depreciation and fees for the whole time the plant had run. We’d done a Civics for Business unit on it as part of the curriculum on Generally Accepted Accounting Principles.

Of course, the people who’d worked there often found themselves shit out of luck when it came to their last paycheck, and sometimes that leased equipment would walk out the door in the days running up to the up-and-out.

I was hungry, like always. Mom didn’t believe in scop, and I didn’t want to piss her off, so I wouldn’t eat out of the vending machines at school. But that meant that if I didn’t remember to throw an apple in my bag, my stomach would growl all the way to lunch.

“Got anything to eat?”

She finished the fifth nail on her left hand and fished in her purse and passed me some leptin gum, which was supposed to enhance satiety and help people like Shirelle stick to the diets they had no need to be on in the first place. I didn’t like to chew it, but my stomach was rumbling. I unwrapped a stick and chewed it. It tasted like caramelized heme proteins, which is to say, cooked blood—in a good way, like a burger—thanks to the transgenic yeast that it was cultured with. My stomach stopped making noise. Maybe it worked (and maybe it was the placebo effect).

“You sure about that up-and-out?” I tried not to sound too interested. Shirelle had a severe case of risk-aversion.

“Girl.” Her side-eye could cut at a thousand yards. But I had been immune to it since ninth grade.

“Come on, Shirelle. Just asking. It’s a daydream.”

Communist parties were one of my favorite daydreams to dream: me and my revolutionary comrades in our funny Karl Marx beards, liberating a whole factory under the noses of the cops and the town, running all those machines and giving away free shit until the feedstock ran out. My dream parties didn’t usually take place in a sheet-metal factory—I liked the idea of taking over a scop factory where they made burgers or candy or ice cream because then I would be the person who gave everyone free candy (or burgers! or ice cream!)—but I’d take sheet metal if it was the only thing going. I could learn my skills there, and also Mama wouldn’t kill me for the scop thing if she found out. Damned health-food crazies.

“Lenae.” She sounded like her own mama when she warned, but I wasn’t scared of her mama, I was scared of my mama, and her mama sounded nothing like mine. Really, the whole basis for our lasting friendship was my immunity to all her secret weapons, which would otherwise burn you down in your shoes the first time she spatted with you.

“It’s a daydream.” Like saying it twice would make it more believable.

“You’re gonna ask someone else if I don’t tell you, aren’t you?”

I didn’t deign to answer. “I’ll hold your phone while you do your other hand.”

She tried the side-eye again, then she put it away and patted the ground next to her. “Hold my phone, then. Go on.” Once she’d done her right thumb, she said, “It’s an up-and-out, yeah, and a

lot of the workers there aren’t happy about it. Wages been really delayed lately, lots of people owed a lot of back pay. Specially people who’re out on sick pay, people got injured on the job, can’t go down to the payroll office in person. So there’s talk.”

“Talk?”

She shook her head. “You’re going to make me spell it out? Talk. They’re going to run some shifts after the place shuts down, sell things out the back door, whatever they can, make back the money they know they’re going to be burned for. In case you don’t understand, Missy, that means no Communist parties.”

I sighed and moved her phone to the last finger. “No party, then.”

“Nope. Forget it, girl. Concentrate on graduating. B students don’t get scholarships.”

This was a running joke between us because A students didn’t get scholarships, either—I mean they did, but at a rate that you’d have to be nuts to count on, like basing your life-plan on winning the lottery every ten years—because there were way, way more kids with broke-ass parents and sharp minds than there were spaces left behind by the dullards who made it into the university on “merit” and by ticking the “no assistance required” box on their applications.

I was an A student anyway.

* * *

She called me that night, after Mama’s lights-out/no-phones blackout time. My little sister Teesha stared at me from her bed when I took the call and mouthed I’m telling. I rolled my eyes at her. She wouldn’t tell. Teesha was still developing her low cunning, and there was plenty of stuff I’d caught her in that she didn’t want me blabbing to Mama in retaliation.

“It’s late,” I whispered.

“Your mama’s crazy.” Shirelle’s mama was strict, too, but not about bedtimes. She was an insomniac, and so were her kids, and she’d taught them her coping skills of doing all their homework, showering, laying out their clothes, and packing their lunches at 2 AM so they could rise 20 minutes before first bell, pee and wash their faces, and be on campus with seconds to spare.

“You call me up after curfew to tell me that? Send a text next time.”

“Antoine called is all. Thought you’d want to know.”

I almost said Who’s Antoine and then I remembered. Her cousin, the sheet-metal worker. “Oh.”

“You want to know what he said?”

“Don’t play games, Shirelle. I’m trying not to wake up my mama. Teesha’s staring at me like she caught me strangling a cat, too.”

“Hi, Teesha!” It was loud enough that Teesha heard it through the earpiece. I winced.

Hi, Shirelle, she mouthed and grinned.

“She says ‘hi.’ Now what is it, Shirelle?”

“Antoine called.”

“You said that.”

“He said the reason the plant is shutting down so fast isn’t just about the tax credits. He says there was a Wobbly in the shop, someone trying to get everyone to sign a union-card.” Union organizing was a fire-able offense, had been since I was a little girl, but that didn’t mean it didn’t happen, and if enough of the workers signed a card, the factory wouldn’t be allowed to stop paying taxes until the California Labor Board had completed its investigation. “Antoine says the other workers are pissed.”

“At the Wobbly?”

“No, stupid, at the bosses. Antoine says that before all this, most of the employees didn’t really give a damn about the Wobbly and her nonsense. But now, it’s got everyone thinking. Got them thinking about making an example out of the plant. They get away with this, next time they’ll be even worse.”

“Hold up, get away with what?”

“Just listen, OK?” I realized she was excited—really excited. “The Wobbly got deported. Born in America and everything. They sent her to Guatemala, said her parents were undocumented when she was born here, so that makes her an anchor baby. Everybody is pissed, like I said, they know it’s just bullshit, an excuse to get rid of her because she’d come sniffing around the shop. Antoine says none of them gave a damn when she was talking about helping them, but when she got deported for trying, out come all this corny talk about it being ‘un-American’ to shut her down.”

“They’re going to let us have a Communist party?”

She made a sound between a squeal and a cheer and Teesha’s eyes got wide. I cut her my sternest look so she didn’t jump right out of bed and tell Mama what she’d just heard, and I realized with a sinking feeling that I was going to have to get my little sister involved if I didn’t want her to rat me out.

Mama would kill me.

The gravity of it fell down on top of me. It was one thing to daydream about this, another to plan it. I’d have to do a lot of googling, using one of those darknet googles that I couldn’t even remember how to reach, so that meant I’d have to get one of the braniac nerds at school to explain it again, which meant that they’d know I was looking up something forbidden and that meant I’d be even more exposed and—

“You aren’t even listening to me, are you, Lenae?”

“Nuh-uh. Sorry, Shirelle. Just thinking it through. Damn! Are we really going to—”

“We are, you don’t get us caught first.”

* * *

Antoine met us at a froyo place off San Fernando, the sketchy part near the dead Ikea that had been all cut up for little market stalls that were mostly empty. I hadn’t seen him since we’d been freshmen and he’d been a senior, and in the years since he’d got strangely grayish, his skin sagging off his face and his hair shot with white, like he was an old man. He looked like he hadn’t been sleeping much, either.

He made a sign at us, a thing with his hands like the kids had done to pass messages around the classroom back when we’d been kids. It took me a second to remember what this one meant: phones down, school cop’s coming. I couldn’t figure out what that was supposed to mean, but Shirelle got it and reached into her purse and shut her phone down. Now I got it, I did the same. We’d both been infected before, of course, drive-by badware that let some creepy rando spy on us through our phones, but then we got more careful. But he wasn’t worried about randos spying through our phone: he was worried about cops.

You think Burbank PD is going to bother with you? I wanted to ask, but fact was, maybe they would. Why not. Once they bought that kind of thing, why wouldn’t they want to use it every chance they got? I probably would.

“Damn.” He looked us up and down, not like a perv, but like a grownup judging a little kid. “You two are so young. I don’t know if this was such a good idea.”

Shirelle gave him an up-and-down of her own. “Antoine, we’re only five years younger than you, fool. Smart, too. Besides, it was Lenae’s idea, not yours.”

That was news to me. Far as I knew, he’d had the idea, told Shirelle, and she’d said, Oh, Lenae said the same thing. But the way he shook his head, I knew it was true—he’d got the idea from me. That made me feel pretty badass, tell the truth.

“OK, OK. Your mama’ll kill me though.”

“Antoine.”

“OK. There’s”—he lowered his voice—“forty-five of us, and one guy, he says he spoke to a Wobbly, they’re pissed about what happened to that girl, and they say they’ll help. We got all skills and hands we need to get it running, but we don’t know how we get the word out without getting popped.”

“Who do you want to reach?” I’d been wondering about this myself. I didn’t really know much about sheet metal, except it was, you know, metal that came in sheets. What would you do with a bunch of that stuff around the house?

“We don’t know either.” Antoine looked anxious. More anxious. He dry-washed those big-knuckled hands. “We can make just about anything we got a file for, and there’s plenty of files out there. You want a fireplace surround or a new truck bumper, we got you covered.”

“Don’t know many people who need a truck bumper,” Shirelle said.

“I know.” Antoine gave her a shut-up look that was brotherly, reminding me that they’d been close since they w

ere little. “There’s all kinds of toys we can make, too, little cars and shit.” He looked at us like, You think that’ll do it?

“I don’t think we’re going to strike terror into the hearts of the investor class by giving away little cars, Antoine, sorry.” Because that was the point, right? Give us all heart, give them sorrows? I hadn’t really thought about where sheet metal fit into that framework.

He shook his head. He knew it, too.

“What were you making?”

“Uber parts.” He shrugged. “Mostly for the vans, you know?”

LA Metro had been using the vans for most of my life, though I could still remember when there had been city buses, before the contract went out to Uber. The vans were boxy and indestructible, covered in some kind of slippery treatment that you couldn’t write on or mark, and which gave off a funky, musty smell like old socks when the sun baked it.

I watched the people mill around the hawkers’ stalls, smelling the Korean tacos and the pupusas cooking and wondering whether any of it was real food instead of scop. I’d skipped breakfast that morning and I was hungry. The food was probably scop, judging from the clientele, who were mostly homeless, and Mama wouldn’t approve, so I didn’t eat, even though my stomach growled. According to my science teachers, single-celled organic protein was safe and healthy—according to Mama, it was a large-scale experiment in feeding mutated bacteria to humans. Mama liked to point out that rich people didn’t eat scop. They didn’t drink coffium, either, but that never stopped Mama. She also had a lapel-pin that read “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.” Mama was one of a kind.

The homeless were accompanied by their inevitable companions, the lovingly tended, rusting, ancient shopping carts. It had been years since it was possible to remove a shopping cart from a grocery store without being caught, but the number of people who used the carts as home, locker, and pack-mule had only grown in the years since, creating fierce competition for the old, dumb carts. These ones looked particularly raggy.

Pirate Cinema

Pirate Cinema Walkaway

Walkaway Little Brother

Little Brother Someone Comes to Town, Someone Leaves Town

Someone Comes to Town, Someone Leaves Town The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow

The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow Super Man and the Bug Out

Super Man and the Bug Out For the Win

For the Win A Place so Foreign

A Place so Foreign Shadow of the Mothaship

Shadow of the Mothaship Return to Pleasure Island

Return to Pleasure Island Party Discipline

Party Discipline Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom

Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom Lawful Interception

Lawful Interception Homeland

Homeland Eastern Standard Tribe

Eastern Standard Tribe Chicken Little

Chicken Little I, Row-Boat

I, Row-Boat Makers

Makers Rapture of the Nerds

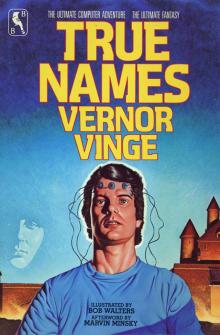

Rapture of the Nerds True Names

True Names