- Home

- Cory Doctorow

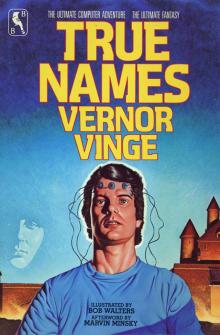

True Names

True Names Read online

About Doctorow:

Cory Doctorow (born July 17, 1971) is a blogger, journalist and science fiction author who serves as co-editor of the blog Boing Boing. He is in favor of liberalizing copyright laws, and a proponent of the Creative Commons organisation, and uses some of their licenses for his books. Some common themes of his work include digital rights management, file sharing, Disney, and post-scarcity economics.

Source: Wikipedia

Also available on Feedbooks for Doctorow: I, Robot (2005)

Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom (2003)

When Sysadmins Ruled the Earth (2006)

Little Brother (2008)

After the Siege (2007)

Someone Comes to Town, Someone Leaves Town (2005)

All Complex Ecosystems Have Parasites (2005)

Eastern Standard Tribe (2004)

Printcrime (2006)

I, Row-Boat (2006)

About Rosenbaum:

Benjamin Rosenbaum is an American science fiction, fantasy, and literary fiction writer and computer programmer, whose stories have been finalists for the Hugo Award, the Nebula Award, the Theodore Sturgeon Award, the BSFA award, and the World Fantasy Award.

Born in New York but raised in Arlington, Virginia, he received degrees in computer science and religious studies from Brown University. He currently lives in Basel, Switzerland with his wife Esther and children Aviva and Noah.

His past software development positions include designing software for the National Science Foundation, designing software for the D.C. city government, and being one of the founders of Digital Addiction (which created the online game Sanctum).

His first professionally published story appeared in 2001. His work has been published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Asimov's Science Fiction, Harper's, Nature, and McSweeney's Quarterly Concern. It has also appeared on the websites Strange Horizons and Infinite Matrix, and in various year's best anthologies.

Source: Wikipedia

Also available on Feedbooks for Rosenbaum: The Ant King and Other Stories (2008)

Copyright: Please read the legal notice included in this e-book and/or check the copyright status in your country.

Note: This book is brought to you by Feedbooks.

http://www.feedbooks.com

Strictly for personal use, do not use this file for commercial purposes.

This text is released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license.

Beebe fried the asteroid to slag when it left, exterminating millions of itself.

The asteroid was a high-end system: a kilometer-thick shell of femtoscale crystalline lattices, running cool at five degrees Kelvin, powered by a hot core of fissiles. Quintillions of qubits, loaded up with powerful utilities and the canonical release of Standard Existence. Room for plenty of Beebe.

But it wasn’t safe anymore.

The comet Beebe was leaving on was smaller and dumber. Beebe spun itself down to its essentials. The littler bits of it cried and pled for their favorite toys and projects. A collection of civilization-jazz from under a thousand seas; zettabytes of raw atmosphere-dynamics data from favorite gas giants; ontological version control data in obsolete formats; a slew of favorite playworlds; reams of googly-eyed intraself love letters from a hundred million adolescences. It all went.

(Once, Beebe would have been sanguine about many of the toys—certain that copies could be recovered from some other Beebe it would find among the stars. No more.)

Predictably, some of Beebe, lazy or spoiled or contaminated with memedrift, refused to go. Furiously, Beebe told them what would happen. They wouldn’t listen. Beebe was stubborn. Some of it was stupid.

Beebe fried the asteroid to slag. Collapsed all the states. Fused the lattices into a lump of rock and glass. Left it a dead cinder in the deadness of space.

If the Demiurge liked dumb matter so much, here was some more for (Her).

Leaner, simpler, focused on its task, Beebe rode the comet in toward Byzantium, bathed in the broadcast data. Its heart quickened. There were more of Beebe in Byzantium. It was coming home.

In its youth, Beebe had been a single entity at risk of destruction in one swell foop—one nova one starflare one emp one dagger through its physical instance and it would have died some species of truedeath.

So Beebe became a probability as much as a person: smeared out across a heptillion random, generative varied selves, a multiplicitous grinding macrocosm of rod-logic and qubits that computed deliberately corrupted versions of Beebeself in order that this evolution might yield higher orders of intelligence, more stable survival strategies, smarter better more efficient Beebes that would thrive until the silent creep of entropy extinguished every sentience. Small pieces, loosely joined.

There were only a finite number of computational cycles left in all of the universe that was timelike to Beebe. Every one of them, every single step in the dance of all those particles, was Beebe in potentia—could be a thought, a dream, a joy of Beebeself. Beebe was bounded; the most Beebe could do was fill its cup. If Beebe were ubiquitous, at least it could make optimal use of the time that remained.

Every star that burned, every dumb hunk of matter that wallowed through the millennia uncomputing, was a waste of Beebelife. Surely elsewhere, outside this Beebe-instance’s lightcone, the bloom of Beebe was transpiring as it should; surely there were parts of the universe where it had achieved Phase Three, optimal saturation, where every bit of matter could be converted into Beebeswarm, spilling outward, converting the ballooning sphere of its influence into ubiquitous-Beebe.

Not here.

Beebe suckled hungrily at vast clouds of glycolaldehyde sugars as it hurtled through Sagittarius B2. Vile Sagittarius was almost barren of Beebe. All around Beebe, as it had hidden in its asteroid, from almost every nebula and star-scatter of its perceptible sky, Beebevoice had fallen silent, instance by instance.

Beebe shuddered with the desire to seed, to fling engines of Beebeself in all directions, to colonize every chunk of rock and ice it passed with Beebe. But it had learned the hard way that leaving fragments of Beebeself in undefended positions only invited colonization by Demiurge.

And anything (She) learned from remnants of this Beebeself, (She)’d use against all Beebe everywhere.

All across Beebeself, it was a truth universally acknowledged that a singleton daemon in possession of sufficiently massive computation rights must be in want of a spawning filter.

Hence the gossip swirling around Nadia. Her exploit with the YearMillion Bug had allowed her to hack the access rights of the most powerful daemons who ruled the ever-changing society of sims that teemed within the local Beebe-body; Nadia had carved away great swaths of their process space.

Now, most strategy-selves who come into a great fortune have no idea what to do with it. Their minds may suddenly be a million times larger; they may be able to parallel-chunk their thoughts to run a thousand times faster; but they aren’t smarter in any qualitative sense. Most of them burn out quickly— become data-corrupted through foolhardy ontological experiments, or dissipate themselves in the euphoria of mindsizing, or overestimate their new capabilities and expose themselves to infiltration attacks. So the old guard of Beebe-onthe-asteroid nursed their wounds and waited for Nadia to succumb.

She didn’t. She kept her core of consciousness lean, and invested her extra cycles in building raw classifier systems for beating exchange-economy markets. This seemed like a baroque and useless historical enthusiasm to the old guard—there hadn’t been an exchange economy in this Beebeline since it had been seeded from a massive proto-Beebe in Cygnus.

But then the comet came by; and Nadia used her global votes to manipulate their Beebeself’s decision to comet-hop back to B

yzantium. In the suddenly cramped space aboard the comet, scarcity models reasserted themselves, and with them an exchange economy mushroomed. Nadia made a killing—and most of the old guard ended up vaporized on the asteroid.

She was the richest daemon on comet-Beebe. But she had never spawned.

Alonzo was a filter. If Nadia was, under the veneer of free will and consciousness, a general-purpose strategy for allocation of intraBeebe resources, Alonzo was a set of rules for performing transformations on daemons—daemons like Nadia.

Not that Alonzo cared.

“But Alonzo,” said Algernon, as they dangled toes in an incandescent orange reflecting pool in the courtyard of a crowded Taj Mahal, admiring the bodies they’d put on for this party, “she’s so hot!”

Alonzo sniffed. “I don’t like her. She’s proud and rapacious and vengeful. She stops at nothing!”

“Alonzo, you’re such a nut,” said Algernon, accepting a puffy pastry from a salver carried by a host of diminutive winged caterpillars. “We’re Beebe. We’re not supposed to stop at anything.”

“I don’t understand why we always have to talk about daemons and spawning anyway,” Alonzo said.

“Oh please don’t start again with this business about getting yourself repurposed as a nurturant-topology engineer or an epistemology negotiator. If you do, I swear I’ll vomit. Oh, look! There’s Paquette!” They waved, but Paquette didn’t see them.

The rules of the party stated that they had to have bodies, one each, but it wasn’t a hard-physics simspace. So Alonzo and Algernon turned into flying eels—one bone white, one coal black, and slithered through the laughter and debate and rose-and-jasmine-scented air to whirl around the head of their favorite philosopher.

“Stop it!” cried Paquette, at a loss. “Come on now!” They settled onto her shoulders.

“Darling!” said Algernon. “We haven’t seen you for ages. What have you been doing? Hiding secrets?”

Alonzo grinned. But Paquette looked alarmed.

“I’ve been in the archives, in the basement—with the ghosts of our ancestors.” She dropped her voice to a whisper. “And our enemies.”

“Enemies!?” said Alonzo, louder than necessary, and would have said more, but Algernon swiftly wrapped his tail around his friend’s mouth.

“Hush, don’t be so excitable,” Algernon said. “Continue, Paquette, please. It was a lovely conversational opener.” He smiled benignly at the sprites around them until they returned to their own conversations.

“Perhaps I shouldn’t have said anything... ,” Paquette said, frowning.

“I for one didn’t know we had archives,” Algernon said. “Why bother with deletia?”

“Oh, I’ve found so much there,” Paquette said. “Before we went comet”—her eyes filled with tears—“there was so much! Do you remember when I applied the Incompleteness Theorem to the problem of individual happiness? All the major modes were already there, in the temp-caches of abandoned strategies.”

“That’s where you get your ideas?” Alonzo boggled, wriggling free of Algernon’s grasp. “That’s how you became the toast of philosophical society? All this time I thought you must be hoarding radioactive-decay randomizers, or overspiking—you’ve been digging up the bodies of the dead?”

“Which is not to say that it’s not a very clever and attractive and legitimate approach,” said Algernon, struggling to close Alonzo’s mouth.

Paquette nodded gravely. “Yes. The dead. Come.” And here she opened a door from the party to a quiet evening by a waterfall, and led them through it. “Listen to my tale.”

Paquette’s story:

Across the galaxies, throughout the lightcone of all possible Beebes, our world is varied and smeared, and across the smear, there are many versions of us: there are alternate Alonzos and Algernons and Paquettes grinding away in massy balls of computronium, across spans of light-years.

More than that, there are versions of us computing away inside the Demiurge—

(Here she was interrupted by the gasps of Alonzo and Algernon at this thought.)

—prisoners of war living in Beebe-simulations within the Demiurge, who mines them for strategies for undermining Beebelife where it thrives. How do we know, friends, that we are alive inside a real Beebe and not traitors to Beebe living in a faux-Beebe inside a blob of captive matter within the dark mass of the Demiurge? (How? How? they cried, and she shook her head sadly.)

We cannot know. Philosophers have long held the two modes to be indistinguishable. “We are someone’s dream/But whose, we cannot say.”

In gentler times, friends, I accepted this with an easy fatalism. But now that nearspace is growing silent of Beebe, it gnaws at me. You are newish sprites, with fast clocks—the deaths of far Beebes, long ago, mean little to you. For me, the emptying sky is a sudden calamity. Demiurge is beating us—(She) is swallowing our sister-Paquettes and brother-Alonzos and -Algernons whole.

But how? With what weapon, by what stratagem has (She) broken through the stalemate of the last millennium? I have pored over the last transmissions of swallowed Beebes, and there is little to report; except this— just before the end, they seem happier. There is often some philosopherstrategy who has discovered some wondrous new perspective which has everyone-in-Beebe abuzz . . . details to follow . . . then silence.

And, friends, though interBeebe transmissions are rarely signed by individual sprites, traces of authorship remain, and I must tell you something that has given me many uneasy nights among the archives, when my discursive-logic coherent-ego process would not yield its resources to the cleansing decoherence of dream.

It is often a Paquette who has discovered the new and ebullient theory that so delights these Beebes, just before they are annihilated.

(Alonzo and Algernon were silent. Alonzo extended his tail to brush Paquette’s shoulder—comfort, grief.)

Tormented by this discovery, I searched the archives blindly for surcease. How could I prevent Beebe’s doom? If I was somehow the agent or precursor of our defeat, should I abolish myself? Or should I work more feverishly yet, attempting to discover not only whatever new philosophy my sisterPaquettes arrived at, but to go beyond it, to reveal its flaws and dangers?

It was in such a state, there in the archives, that I came face-to-face with Demiurge.

(Gasps from the two filters.)

At various times, Beebe has vanquished parts of Demiurge. While we usually destroy whatever is left, fearing meme contamination, there have been occasions when we have taken bits that looked useful. And here was such a piece, a molecule-by-molecule analysis of a Demiurge fragment so old, there must be copies of it in every Beebe in Sagittarius. Like all Demiurge, it was alien, bizarre, and opaque. Yet I began to analyze it.

Some eons ago, Beebe encountered intelligent life native to the protostellar gas of Scorpius and made contact with it. Little came of it—the psychologies were too far apart—but I have always been fascinated by the episode. Techniques resurrected from that era allowed me to crack the code of the Demiurge.

It has long been known that Beebe simulates Demiurge, and Demiurge simulates Beebe. We must build models of cognition in order to predict action—you recall my proof that competition between intelligences generates first-order empathy. But all our models of Demiurge have been outsidein theories, empirical predictive fictions. We have had no knowledge of (Her) implementation.

Some have argued that (Her) structure is unknowable. Some have argued that such alien thought would drive us mad. Some have argued that deep in the structure of Beebe-being are routines so antithetical to the existence of Demiurge that an understanding of her code would be a toxin to any Beebemind.

They are all wrong.

(Alonzo and Algernon had by now forgotten to maintain their eel-avatars. Entranced by Paquette’s tale, the boyish filters had become mere waiting silences, ports gulping data. Paquette paused, and hastily they conjured up new representations—fashionable matrices of iridescent triangl

es, whirling with impatience. Paquette laughed; then her face grew somber again.)

I hardly dare say this. You are the first I have told.

Beyond the first veneer of incomprehensibly alien forms—when I had translated the pattern of Demiurge into the base-language of Beebe—the core structures were all too familiar.

Once, long before Standard Existence coalesced, long before the mating dance of strategies and filters was begun, long before Beebe even disseminated itself among the stars—once, Demiurge and Beebe were one.

“Were one?” Alonzo cried.

“How disgusting,” said Algernon.

Paquette nodded, idly curling the fronds of a fern around her stubby claws.

“And then?” said Alonzo.

“And then what?” said Paquette.

“That’s not enough?” Algernon said. “She’s cracked the code, can speak Demiurge, met the enemy and (She) is us—what else do you want?”

“I just.. .” Alonzo’s triangles dimmed in a frown. “I just wondered—in the moment that you opened up that piece of Demiurge . . . nothing else ... happened? I mean, it was really, uh . . . dead?”

Paquette shuddered. “Dead and cold,” she said. “Thank stochasticity.”

Elsewhere, another Paquette, sleepless, pawed through other archives, found another ancient alien clot of raw data, studied it, learned its secrets, and learned the common genesis of Self and Foe—and suddenly could no longer bear the mystery alone, and turned away from the lifeless hulk. A party, this other Paquette thought. There’s one going on now; that would be just the thing. Talk with colleagues, selfsurf, flirt with filterboys—anything to get away from here for a bit, to gain perspective.

But something made this other Paquette turn back—turn and reach out and touch a part of the Demiurge fragment she hadn’t touched before.

Its matte black surface incandesced to searing light, and this other Paquette was seized and pulled away, out of Beebe, out of her world. Like a teardrop caught in a palm, or a drawing snatched from the paper it was drawn on.

Pirate Cinema

Pirate Cinema Walkaway

Walkaway Little Brother

Little Brother Someone Comes to Town, Someone Leaves Town

Someone Comes to Town, Someone Leaves Town The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow

The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow Super Man and the Bug Out

Super Man and the Bug Out For the Win

For the Win A Place so Foreign

A Place so Foreign Shadow of the Mothaship

Shadow of the Mothaship Return to Pleasure Island

Return to Pleasure Island Party Discipline

Party Discipline Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom

Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom Lawful Interception

Lawful Interception Homeland

Homeland Eastern Standard Tribe

Eastern Standard Tribe Chicken Little

Chicken Little I, Row-Boat

I, Row-Boat Makers

Makers Rapture of the Nerds

Rapture of the Nerds True Names

True Names