- Home

- Cory Doctorow

The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow Page 5

The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow Read online

Page 5

She clucked her tongue and crossed her eyes. “Don’t be stupid. There’s room for both of us there. I’m not going to put you out of your bed. Get in.”

I hesitated.

“Get in!” she said, clapping her hands.

I turned away and awkwardly stripped down to my underpants and shirt. I worried again that I might smell. I didn’t wash my clothes all that often. They were wicking and dirt-shedding and had impregnated antibacterials, so I didn’t see why I should. But maybe I smelled. The cultists wouldn’t say anything. Wireheads didn’t notice that kind of thing.

She clapped her hands again and pointed at the pillow. “March, young man!”

Then I was whirling back in time. That was what Dad used to say when I was dragging my ass around. Had I told her that? Did she know it anyway? Had she guessed? Was it a coincidence?

She repeated herself and pointed. I crawled into the bed. The pack bounded in after me, assuming their usual positions all around me, snuggling and burrowing among the pillows. She laughed.

A moment later, the pillows shifted around me as she climbed in next to me. I tried to press myself up against my wall, giving her as much space as possible, but she gathered me in her arms and squeezed me like a teddy bear.

“Good night, Jimmy,” she said. Her face smelled of soap and her hair smelled of woodsmoke. It tickled my cheeks. She kissed the top of my head.

A weird thing happened then. I stopped thinking about her being naked. I stopped thinking about her being my old friend Lacey. Suddenly, all I could think about was how good this felt, being held to a soft bosom, enfolded in strong arms. Dad hugged me plenty. But I didn’t remember my mother. She’d died not long after I was born. Poisoned by Detroit. She hadn’t eaten her yogurt, didn’t get her microbes, and so her liver gave out. Dad barely talked about her, and the photos of her had vanished with Detroit itself, consumed by some wumpus and turned into arable land.

Lacey squeezed me again, and I found that I was crying. Silently at first, then I must have let out a whimper because she went, “Shhh, shhh,” and squeezed me harder. “It’s OK,” she murmured into my hair, and words like that, and rocked me back and forth, and then I was crying harder.

I cried myself out there in the pillows, in Lacey’s arms. I don’t know what I wept for, but I remember the feeling as not altogether sad. There was some joy there, a feeling of homecoming in the arms of my old friend. The pack snuggled in among us, and they were ticklish, so soon we were both laughing and rocking back and forth.

“Good night, Lacey,” I said.

“Good night, Jimmy,” she said. She kissed the top of my head again and squeezed me harder and I let myself relax in her arms.

The wireheads don’t mind the occasional houseguest, but anyone who’s going to actually live in the settlement needs to join the cult. They don’t want any violent, emotional, unpredictable people running around, making things difficult for them. The deal is a simple one: get the wire in your head, get free food, shelter, and community forever. Don’t get the wire in your head and you have to get out of town.

You’d be surprised at how many people don’t want to play along with this system (I guess I count as one of those people). The cult’s gotten pretty good at spotting freeloaders who want to live in the peace and prosperity of the cult but don’t want to join up. These people seem to think that so long as they’re doing their share of the work, they should be able to stick around. What they don’t understand is that the work isn’t the important part: robots can do the heavy lifting, as much as we let them do of it.

The important thing is the stability. Here in wirehead country, nothing important ever changes. New people come in. Old people die. Babies are born. Kids go to school—I went with them for a little while, in my wirehead days, but I decided I didn’t need to keep going to classes after three or four years, and no one seemed to mind. No one minds what anyone else does, once you’re a wirehead. Since we can all feel each others’ emotions, it’s impossible to resent someone without him knowing about it, and it’s impossible to feel guilty without letting others know it. Your whole attitude toward your neighbors is on permanent display, visible from a mile off. My own antenna seems to radiate a calm acceptance no matter what I’m feeling, and lets me know what others are feeling without swamping me with their emotions.

The work gets done. “Progress” never happens. We’ve banished progress, here in the wirehead cult. That’s OK by me, I suppose. Who needs it?

“So I had been living in Florida, up near Jacksonville, in wiki country,” Lacey said, over our breakfast. I kept a larder of fresh fruit in the maintenance space under the stage, and Lacey had been glad to help me slice up a couple of delicious fruit salads. I’d put up some yogurt a few days before and it was mature enough to pour overtop, with some sunflower seeds left over from the last autumn. “The city was good, but it got to me, all that change, all the time. I tried to garden a little patch of it, just a little spot where I could put up a house, but there were so many trolls who kept overwriting my planning permission with this idea for a motorcycle racing track. I’d revert their changes, they’d revert back. Then one of the Old Ones would come by and freeze my spot for a month and lecture us. Then they’d be back at Day 31. I only met them face to face once. I’d pictured them as old Florida bikers, leathery and worn, but they were teenagers! Just kids.”

I looked away, at the blue sky overhead, visible through the riotous colors of the leaves.

“Sorry,” she said. “You know what I mean, though. They were like, eight sixteen-year-olds, and they’d built their bikes to burn actual hydrocarbons. These things made so much goddamned noise! Your old mecha was quieter! They rode them up to my house one day, left all six in my garden, among my flowers, growling, and rang my doorbell.

“I had built a little gypsy caravan with flower-boxes and bright paint, all prefab vat-grown woodite, impervious to weather and bugs, watertight at the seams, breathing through a semipermeable roof and floor. It was a really nice piece of engineering—my parents would have liked it!

“I answered the door and they pointed to their motorcycles and explained that they’d spent an entire year building and tuning them and that my little house was the only thing stopping them from building a racetrack. They wanted me to move the house to somewhere else. They were extra pissed because my house had wheels, so how hard could it be to relocate? They even offered to find me somewhere else, get me a tow. I told them no, I liked it there, liked my garden (what was left of it), liked the creek down the hill from me, liked my view of the big city down the other side of the hill, all its lights.

“They told me that their parents had lots of money and they could get me a real big place somewhere up high in the city, maybe even put my caravan on a roof there.” She stopped talking while we picked our way down a hillside. We were headed for my own creek, which was cold and brisk, but still swimmable, for a week or two. I’d brought a bar of soap.

“I told them to get off my land. I also recorded them from my front window as they shouted things at me and threw stuff at my door. It turned out to be dead animals. They left a dead rabbit or squirrel on my doormat every day for a week. I added pictures to the Discuss page for the zoning, and the Old Ones were properly affronted and froze their editing privileges.

“But they didn’t let up. They had a whole army of sock-puppets they were paying in Missouri, a boiler-room outfit where they’d do actual work on the wiki, improve it a lot, build up credibility and make themselves very welcome, then come and edit my zoning. It got so I was doing nothing but staying home all day and reverting and arguing with these guys.

“Then I went away for a couple days—there was a barbecue festival in a big field outside of town and I got invited to compete, so I was working over a smoker there, and when I got back, guess what?”

“Your caravan was gone and they were racing motorcycles where it used to be.”

“Exactly,” she said. “Exactly. They’d k

nocked down the trees, dammed the stream, paved everything, put in half-pipes. Even if I changed the zoning back, I wouldn’t want to live there again.”

“I woulda been pissed,” I said, getting down to my skin and jumping into the stream, sputtering and blowing. Normally I’d have waded in a few millimeters at a time, but I was still uncomfortable being nude in front of her, so I just plunged. She followed suit.

“You’d think, huh?” she said. “But I was just resigned at that point. I moved to the city, which had its own charms. Remember that they said they could get me a rooftop? Well, it turns out that roofs were easy to get. Not many people want to sleep on the ninetieth floor of a tower, but I found it as peaceful as anything. I strung up my hammock and put up my tents and settled in to love my view.”

Sometimes it was hard to remember that this was Lacey Treehugger, the girl who’d thought that all concrete was a sin. Ninety floors up! Damn.

There were more people coming down to the creek. Double damn. Lacey had been there three days and we had managed to avoid my neighbors the whole time, but my luck had run out.

They had the typical wirehead look: one-piece, short-sleeved garments that shed dirt, so they glowed faintly. Stripes and piping were the main decoration. Someone had designed this outfit in the early days of the cult and no one had ever redesigned it. Of course not. Why change anything around here?

There were three of them. I recognized them at once: Sebastien, a guy in his twenties whom I’d known since he was a baby; Tina, an older woman with teak-colored skin; and Brent, her son, who was eleven, the same as me, sort of.

“Hello there,” Sebastien said. I felt the tickle of their emotions from the vestiges of my antenna, a kind of oatmeal-bland wash of calm nullity. “Haven’t seen you in a few days.” He noticed Lacey and squinted at her. She had sunk down so that only her round face stuck up out of the sluggish water. “Hello to you, too,” he said. “I’m Sebastien, this is Tina and Brent.” They all waved, except for Brent, who was bending down and examining a frog he’d found on a flat rock.

“This is my friend Lacey,” I said. Sebastien drove me crazy. He was born and bred to the cult and always wanted to talk to me about how much better life was now that I was living with the wireheads. He was the kind of zealot who made me worry that if I didn’t match his enthusiasm that he’d try to figure out if my antenna was working properly. Talking to him always put me on my guard.

Lacey waved.

“We’re here for a swim,” he said, like it wasn’t obvious. He didn’t ask if we minded—no wirehead would—but instead just started stripping down to the bathing trunks he wore under his jumpsuit, giving me an accidental glimpse of his bony ass. Tina did the same, taking his hand and squeezing it, then Brent struggled out of his. Tina and her ex-husband had Brent and then split when he was still a baby, one of those weird, calm wirehead divorces, so mellow they might as well be happening underwater.

They slipped into the water with us and I knew I was going to have to say something. “I’m sorry,” I said, “but we’re not wearing anything in here. Do you mind looking away while we get out?”

Sebastien and Tina had made it in to their shins, their bodies broken out in gooseflesh from the icy, bracing water. “Oh, Jimmy,” Tina said. “We’re sorry.” All three of them caught her sadness and looked downcast. Reflexively, I looked sad too. Gradually, they caught the larger emotion of the group, still perceptible at this distance, and got happier again.

“Don’t worry about it,” I said once the sun had risen on their moods again. “It was inconsiderate of us. I didn’t think anyone else would be down by the river on a day like this.”

“We like it cold,” Sebastien said. “Wakes up the body.” Then Brent took a few toddling steps into the water, slipped, and splashed them. They laughed and splashed him back. There was a moment of frenzy as they caught each others’ surprise and glee, and then it, too, dampened down.

“Well, we’re just about done here,” I said.

“Nice to meet you,” Lacey said. They’d turned their backs, but I caught Brent sneaking a peek before he looked away, too.

“Nice to meet you, too,” Tina said. “You be sure and come by the general meeting tonight, all right?”

I grunted as noncommittally as I could, while pulling on my jumpsuit over my wet legs. It wicked away the wet as I struggled into it. I just wanted to get away from there—they were curious about Lacey, I could tell that even without a fully functional antenna.

Lacey just pulled her smartcloak over her head and let her boots conform themselves to her feet. We had walked idly and slowly to the river, but we hurried away.

“I’m not supposed to be here, am I?” Lacey said.

“No,” I said. “Yes.” I helped her up onto the side-trail that I used when I didn’t want to talk to anyone. “It’s complicated. They’re going to want you to get wired, or leave.”

“And getting wired—you wouldn’t recommend it?”

I shrugged. “They’re nice people. If you had to choose a group of people to share your state of mind with, they’d be a pretty good choice.”

“But you don’t think it’s a good idea.”

I shrugged again. “I let them put a wire in my head,” I said.

“Your brain ate it, though.”

I looked around, suddenly paranoid. There was no one. “Shhh. Yes, but I didn’t know that my brain would eat it when I let them install it.”

“So why’d you do it?”

I thought back. “I was a kid,” I said at last. “I’d just lost my Dad and my home. They were nice to me. They said that they’d leave me alone once I had the wire fitted. That was all I wanted.”

“Did you like it?”

“Having a wire? Well, not the worst thing in the world, having a wire. I never felt lonely. And when I was sad, it passed quickly. I think it would have been a lot harder without it.”

“So you think it’s therapeutic, then? Maybe I should get one after all.”

I turned around and took her hands. “Don’t, OK? Please. I like you this way.”

We got home and sat down in the theater seats. I thought we’d talk about it, but we seemed to have run out of words. I wished for a moment that we had matching antennae so I could know what she was feeling. That was pretty weird.

“Show me this play,” she said. “I fell asleep the other night.”

So I started it up. I’d done a major, three-year-long maintenance project on it that had just wrapped up, so it was running as good as new. I was proud of the work I’d done. I wished that Dad could see it. Lacey was nearly as good.

We sat through the opening scene, rotated around the arc by 60 degrees, and went through the change to the Roaring Twenties. The family’s kitchen was now filled with yarn-like wires coming off the ceiling light and leading to all the appliances. Dad was wearing a bow tie now and fanning himself with Souvenir of Niagara Falls fan. Dad wants to show us all his new modern appliances, so they all switch on and start flapping and clacking while frenetic music plays in the background. Then a “fuse” blows—I looked this up, it means that he overloaded a crude breaker in the power-sup-ply—and the whole street goes dark. A neighbor threatens to beat him, but then “Jimmy”—yes, Jimmy again—changes the fuse and the lights come back.

Mom and Sister are getting into costume—there’s a Fourth of July party that night—and Dad has to join them, but he gets us to sing his song. I noted that Lacey tapped her toe as we went around the arc, and it made me feel very good.

After the show, I made us diner and Lacey told me more funny stories from the road. Then we crawled into bed and she enfolded me in her arms. We’d done that every night. I didn’t cry anymore, and it felt so good. Like something I’d always missed.

“They’re going to come for you,” I said, lying with my eyes open, feeling her arms around me.

“They are, huh?”

“Put a wire in your head.”

“And you don’t think I

should do that.”

“I’ll go with you.” I swallowed. “If you want.”

She squeezed me harder. “I don’t think you’ll be able to carry this thing, do you?”

“I don’t mind.”

“Liar. You’ve been taking care of this thing for twenty years, Jimmy!”

“That was when I thought that Dad would come back for it. Doesn’t seem like he’ll come back now. Stupid terrorists.”

“Who?”

“The assholes who attacked Detroit. Whoever they were.” I noticed that she’d stiffened a little. “I thought they were thieves at first, after our stuff. But from what you say, it sounds like they were terrorists—they just wanted to destroy it all. We probably had the last mountain of steel-belted radials in the world, you know?”

She didn’t say anything for a bit. “I can go in the morning. We can stay in touch.”

“I want to go with you.” I surprised myself with the vehemence of it. “I need to get away from here. I need to get away from this thing” I punched out at the wall at the edge of the bed, giving it a hard thump and sending the pack scurrying around in circles. “Fuck this thing. It’s a prison. It’s stuck me down here. Just another one of Dad’s stupid ideas.”

“You shouldn’t talk about your Dad that way. He was—”

“What? He was an asshole! Look at me! Do you think I want to be like this forever?”

“You told me that you thought you’d found a cure for it—”

I laughed. “Sure, sure. But I’ve thought that for twenty years. Nothing’s worked.”

She hugged me tighter. “It’s not all bad, is it? It could be worse. You could be getting old, like me. I get what I can out of the neutraceuticals, but you know, it gets harder every day. I can’t walk as far as I used to. Can’t see as well. Can’t hear as well. I’m getting wrinkled, I keep finding grey hairs—”

“Come on,” I said. “You’re a beautiful woman. You got to grow up. I’m just a little kid! I’m going to stay a little kid forever. You got to change. Not just change, either—progress! You got to progress, to get better and smarter and wiser and, you know, more!”

Pirate Cinema

Pirate Cinema Walkaway

Walkaway Little Brother

Little Brother Someone Comes to Town, Someone Leaves Town

Someone Comes to Town, Someone Leaves Town The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow

The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow Super Man and the Bug Out

Super Man and the Bug Out For the Win

For the Win A Place so Foreign

A Place so Foreign Shadow of the Mothaship

Shadow of the Mothaship Return to Pleasure Island

Return to Pleasure Island Party Discipline

Party Discipline Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom

Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom Lawful Interception

Lawful Interception Homeland

Homeland Eastern Standard Tribe

Eastern Standard Tribe Chicken Little

Chicken Little I, Row-Boat

I, Row-Boat Makers

Makers Rapture of the Nerds

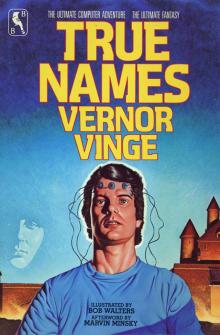

Rapture of the Nerds True Names

True Names