- Home

- Cory Doctorow

Walkaway Page 12

Walkaway Read online

Page 12

She put on fresh clothes—the new goretex printer/cutter was up, and it was a treat to step into something dry, breathable, and perfectly fitting whenever you wanted. She went to the meeting.

She didn’t have to say a word.

Ten minutes later, sputtering Jackstraw was shown the door and politely asked not to return. They filled his pack and gave him two sets of goretex top-and-bottoms. Anything less would have been unneighborly.

[vii]

Limpopo’s dirty secret was that she had been scraping the B&B’s production logs and dumping them into a homebrewed analytics system she frankensteined from the world of gamified motivational bullshit. Every now and again, she’d run the logs and look at how far ahead of everyone else she was. She especially liked to look at the stats charts when she lost an argument about how something could be done.

Not because it soothed her ego. It was weirder. When Limpopo lost an argument, the fact that she’d done more than the person she lost to felt great. Being a walkaway meant honoring everyone’s contributions and avoiding the special snowflake delusion. So losing to someone over whom, in default, she’d have rank to pull made her a fucking saint. No one was a special snowflake, but she was better at not being a special snowflake than everyone.

Looking at those charts gave her almost exactly the same feeling of shame and pleasure that she got from looking at porn. It was raw self-indulgence, something that exclusively fed her most immature and selfish desires. It was catnip for Limbic Limpopo, and the more she fed that greedy maw, the more she was able to tell it to shut up and let Long-Term Limpopo drive the bus. At least, that’s what she told herself.

* * *

Now he was called Jimmy and decked out in stuff that made goretex look like uncured rat-hides stitched with dried grasses. He was enjoying himself.

“You should see the numbers,” he said to his buddies. Unlike the B&B, who came in every shade, all of his friends were whities, except for one guy, who might have been Korean. “She’s the queen of this place.” He shook his head—his neck was bull-like, to match his cartoon biceps. “Shit, Limpopo, you really are the queen. From now on, you and a guest can stay here whenever, any room in the house. Full kitchen and workshop privileges. I want you to join our board. We need someone like you.”

Etcetera had been hanging back, breathing fast at first, then slowing. She wondered if he’d do something stupidly physical. That would be a waste.

There was a narrative she was supposed to participate in, a hole Jimmy made for her to step into. Either she threw her lot in and legitimized his coup—she doubted that he’d put store in that happening—or, better, make a stand, let him humiliate her the way she’d supposedly humiliated him. The only way to win was not to play.

She stood.

He tried to draw her by talking about how they’d expand capacity by separating leeches from leaders, take care of the craphounds by giving some beds to charity every month. She stood mute.

The longer she stood, the more freaked Jimmy was. The longer she stood, the more people drifted out to find out what was up. It was like a physical replay of the old online showdown.

“He just showed up and declared it a done deal,” said Lizzie, who’d been with the B&B since the beginning, hammering surveying stakes where the network told her. “No one wanted to fight, right? He had a stupid powerpoint with our stats, scraped off the public repos, showing everyone here would go on having the same privileges we’d always had, because we were putting enough work in.”

“Yeah,” said Grandee, who was short, old, and weird, but whom Limpopo liked because he was a good listener, with something broken inside that she’d never asked about but felt protective about nonetheless. “He talked about waves of new walkaways headed this way, a massive uptick that would overwhelm us unless we had some system to allocate resources. He had videos about places where it had happened.”

She nodded. She’d heard about places where numbers had swollen faster than could be absorbed; well-established taverns becoming crowded, then overcrowded, then catastrophic. There’d even been violence—rare, but luridly reported in default press that trickled back into walkaway. Lurid or not, it was disgusting. There was an arson, with a miraculous body count of zero (the photos had been such a strong trigger for Limpopo that she’d told her readers to filter any more reports of it).

“Okay,” she said. More people trickled out.

It was cold. Their breath fogged, reminded her of the onsen’s steam.

The crowd on Limpopo’s side grew. An invisible switch flipped and anyone who didn’t stand with Limpopo’s group implicitly stood against it—not just going with Jimmy’s group because it was easiest and what did it matter, really—but actually standing against Limpopo’s group and everything they’d stood for.

Limpopo’s pack had survival gear that could keep her alive for a day in the woods, come the worst. She fired up her stove, feeding it twigs until the fan drove the heat from their combustion to gas-phase transition and the dynamo that powered the battery whirred and the idiot light came on, telling her the stove was doin’ it for itself.

She made tea. She had a book of fold-up teacups, semirigid plastic pre-scored for folding into mugs with geometrical handles. She loved them, they looked like low-resolution renders of a cup, leapt off a screen into physical space. The teapot was a pop-up cylinder she filled with snow, trekking to an untouched fall on the clearing’s edge, watched suspiciously by Jimmy and his crew, and with bemusement by her people.

Once the tea was brewed, she poured and passed it around. It turned out there were others with folding cups, some with super-dense seed-bars glued with honey from the B&B’s apiary, rock-hard and dense as ancient suns, the delicious taste of home for anyone who lived at the B&B.

Why did they have this stuff squirreled about their persons? Because as soon as someone started talking about rationing, the urge to hoard became irresistible.

As soon as she shared, the hoarding impulse melted. You got the world you hoped for or the world you feared—your hope or your fear made it so. She emptied her pack, found moon-blankets and handed them to people without coats. She took off her coat so she could get at her fleece and gave it to a shivering pregnant woman, a recent arrival whose name she hadn’t gotten, then put her coat back on before she started to freeze. The coat was enough, even standing still. It had batteries for days and for temperatures more hazardous than this.

This triggered a round of normalization of outerwear, a quiet crowd-wide check-in—at least fifty, nearly the full complement of B&B long-termers—and swapping of gear. The impromptu ritual started off solemnly but turned hilarious, laughter in the face of Jimmy and his tactical meathead greedhead assholes.

They didn’t know what to make of this. Jimmy had a trapped-animal look she recognized from earlier, a near-breaking-point face she didn’t like at all. Time to make a move.

“Okay.” Though she spoke quietly, her voice carried. There was an instant hush. “Where do we build? Anyone?”

“Build what?” Jimmy demanded.

“The Belt and Braces II,” she said. “But we’ll need a better name. Sequels suck.”

“What the fuck are you talking about?” Definitely close to the breaking point.

“You’ve taken this one away. We’ll make a better one.”

“Are you shitting me? You’re going to give up, without a fight?”

“We’re called walkaways because we walk away.” She didn’t add, you dipshit. It didn’t need to be said. “It’s a huge world. We can make something better, learn from the errors we made here.” She stared. His mouth was open. She had his fucking number. Any second later, he would talk—

“That’s—”

“Of course,” she steamrollered over him as only someone who has to work in every conversation not to interrupt can, “there’s a good chance that you and your friends will crash this place. When you abandon it, we’ll come back and use it for feedstock and raw materials.” S

he did her pausing trick again, waiting—

“You’ve—”

“Assuming you don’t burn it down or loot it.” Would he fall for a third time? Yes, he would—

“I wouldn’t—”

“You probably plan on keeping our personal effects, now that you’ve nationalized our home for the People’s Republic of Meritopia?” If you bite down the sarcasm every time it rises, it gets crafty. This one hit him so square in his mental testicles you could hear it. Four times she’d stepped on his words before he could get them out and then, wham, pasted him. That felt so good it was indecent. But fuck it. The prick had stolen her house.

“Look—” This time he did it to himself, couldn’t believe that he would get a word in, tripped over his tongue. His own douchebros sniggered. He was comprehensively pwned, metaphorical pants down. He turned bright red. “We don’t have to do this—”

“I think we do. You’ve made it clear that you’re so obsessed with this place that you’ll impose your will on it. You have shown yourself to be a monster. When you meet a monster, you back away and let it gnaw at whatever bone it’s fascinated with. There are other bones. We know how to make bones. We can live like it’s the first days of a better world, not like it’s the first pages of an Ayn Rand novel. Have this place, but you can’t have us. We withdraw our company.”

A bright idea occurred to him. “I thought there was no leader. What’s this ‘we’ shit? Can’t you see she’s manipulating you all—”

She raised her hand. He fell silent. She didn’t say anything, kept her hand up. Etcetera, bless him, put his hand up next. Moments later, everyone had one hand up.

“We took a vote,” she said. “You lost.”

One of his skeezoids—what must he have promised them, she wondered, about this place—gave a heartfelt “Daaaamn.” Had she ever won.

“Do we get our stuff, Jimmy?”

Bless his toes and ankles, he said: “No.” Set his jaw, made a mutinous chin. “No. Fuck all y’all.”

It would be a cold night, but not too cold. They knew where the half-demolished buildings they could shelter in were, and were carrying lots of this and that. Once they got into range of walkaway net, they would tell the story—the video was captured from ten winking lenses she could count—and rely on the kindness of strangers. They’d rebuild.

Figures, she didn’t have to say. However awful things got that night. However much work they’d do in the years that followed. However many sore muscles and blistered hands and busted legs they endured, everyone would remember Jimmy. Remember what happened when the special snowflake disease ran unchecked. They’d build something bigger, more beautiful. They’d avoid the mistakes they’d made the last time, make exciting new ones instead. The onsen would be amazing. Their plans had been forked a dozen times since they’d shipped, some of the additions were gorgeous. As she started putting one foot in front of the other, her mind went to these thoughts, the plans took form.

The girl, Iceweasel, fell into step. They walked, crunch, crunch, huff, huff, through the woodland. “Limpopo?”

“What’s on your mind?”

“Don’t take this the wrong way, but are you fucking kidding me?”

“Nope.”

“But this is crazy! You made that place. You just let him take it!”

“Wasn’t mine, I didn’t make it. I didn’t let him take it.”

She practically heard the very refined eye-roll with breeding, money, and privilege behind it. Someone like Iceweasel never had to walk away from anything she had a claim to. The army of lawyers and muscle saw to it. This was a horizon-expanding journey for her. Practically a good deed. Limpopo yawned to cover her smile before it could embarrass Iceweasel.

“You and I both know that you put more work into that place than anyone else.”

She shrugged. “Why does that make it mine?”

“Come on. So it’s not yours-yours, but it’s still yours. Yours and everyone else’s or however the orthodox high church of walkaway insists that we discuss it, but don’t be ridiculous. Mr. Tough Guy didn’t do shit for that place, you guys did everything, and you handed it over without a fight.”

“Why would fighting have been preferable to making something else like the Belt and Braces, but better?”

“This is the world’s most pointless Socratic dialog, Limpopo. All right: if you’d fought, you’d have had the Belt and Braces. Then, if you wanted somewhere else, someplace better, you could have built that, too.”

Limpopo looked over her shoulder. They’d fallen into a ground-eating stride while talking, left the column of refugees behind. She unrolled the insulated seat of her coat and settled down on a snowy rock, making sure the flexible foamcore spread below her butt and legs, ensuring the snow didn’t touch anything except it. Iceweasel followed, and did a good job. Limpopo liked to see people who were good at stuff, who paid attention and practiced, which is all the world really asked.

“I’m not trying to be a jerk,” Limpopo said. She pulled a vaper out and loaded it with decaf crack, which would keep her going for the three hours she’d need to reach the next walkaway settlement. Iceweasel took two hits, then she took one more, even though everything after that first bump was inert, wouldn’t do anything except turn your pee incandescent orange. The psychological effect of hitting the pipe was comforting. She did one more.

“I’m not trying to be a jerk,” she said again, admired the puffs of crispy fog that floated before her face, thrilled at the weight that lifted from her muscles, the sense of coiled power. Both of them giggled with stoned acknowledgement of the inherent comedy. “You have to understand that if I put this into your frame of reference, the frame of reference you want me to put it in, it doesn’t make any sense.

“The only way this makes sense is if I insist that I can’t ‘have’ more than one B&B. The only claim I can have is that I’m doing it good by staying there and vice versa. What good do I do to the B&B once I leave? What good does it do me? If I’ve got somewhere to stay, I’m good.”

“Yeah, yeah. What about other people who want to stay at the B&B, but have to deal with Captain Asshole and his League of Prolapses to get a bed?”

“I plan on building somewhere else. I hope they help build it. I hope you stay and help.”

“Of course. We’re all going to build it. But when they come and take that away—”

“Maybe I’ll go back to the B&B. It doesn’t matter. The important thing is to convince people to make and share useful things. Fighting with greedy douches who don’t share doesn’t do that. Making more, living under conditions of abundance, that does it.”

The look she got from the younger woman was so shrewd that she came clean. Or maybe it was the crack. “I’ll admit it. I felt the B&B was ‘mine,’ like my work on it entitled me to it. The truth is even if you’re right and I did more than others, that doesn’t mean I could have built it without them. The B&B is more than any one person could build, even in a lifetime. Building the B&B, running it, that’s a superhuman task, more than a single human could do. There are lots of ways to be superhuman. You can trick others into thinking that unless they do what you tell them, they won’t eat. You can cajole people into doing what you want by making them fear god or the cops, or making them feel guilty or angry.

“The best way to be superhuman is to do things that you love with other people who love them, too. The only way to do that is to admit you’re doing it because you love it and if you do more than everyone, you’re still only doing that because that’s what you choose.”

Iceweasel stared at her gloves, flexing her fingers minutely, which made Limpopo want to do the same, sympathetic fidgeting. “Doesn’t it depress you? All that work?”

“A little. But it’s exciting. The thing about starting over is you get to see the thing grow in leaps. Once it’s built, all you get is tweaks, new paint, and minor redecorations. Seeing a piece of blasted ground and a pile of scavenge leap into the sky and become a pl

ace, having its software get into you and you get into it, so wherever you are, no matter what you’re doing, there’s something you can do to make it better, that’s amazing.” The crack was fizzling, and as always, she felt fleeting melancholy as it bade her farewell. “Not to change the subject, but—”

The rest of the group was coming. In a minute or two they’d be marching.

“You know this,” she said, hefting her vaper, which Iceweasel deftly relieved her of, taking another bump and blowing a plume of fragrant steam, like pine tar and burned plastic, a homey smell. “That feeling of happiness and intensity you get? Did you ever wonder whether it was something we were meant to experience more than fleetingly? Take orgasms. If you had an orgasm that didn’t stop, it’d be brutal. There’d be a sense in which it was technically amazing, but the experience would be terrible. Take happiness now, that feeling of having arrived, having perfected your world for a moment—could you imagine if it went on? Why would you ever get off your ass? I think we’re only equipped to experience happiness for an instant, because all our ancestors who could experience it for longer blissed out until they starved to death, or got eaten by a tiger.”

“You’re still high,” Iceweasel said.

She checked. “Yup.” The group was on them. “It’s going away. Let’s move.”

They fell into the column and marched.

3

takeoff

[i]

The ashes of Walkaway U were around Iceweasel. It was an unsettled climate-ish day, when cloudbursts swung up out of nowhere, drenched everything, and disappeared, leaving blazing sun and the rising note of mosquitoes. The ashes were soaked and now baked into a brick-like slag of nanofiber insulation and heat sinks, structural cardboard doped with long-chain molecules that off-gassed something alarmingly, and undifferentiated black soot of things that had gotten so hot in the blaze that you could no longer tell what they’d been.

Pirate Cinema

Pirate Cinema Walkaway

Walkaway Little Brother

Little Brother Someone Comes to Town, Someone Leaves Town

Someone Comes to Town, Someone Leaves Town The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow

The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow Super Man and the Bug Out

Super Man and the Bug Out For the Win

For the Win A Place so Foreign

A Place so Foreign Shadow of the Mothaship

Shadow of the Mothaship Return to Pleasure Island

Return to Pleasure Island Party Discipline

Party Discipline Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom

Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom Lawful Interception

Lawful Interception Homeland

Homeland Eastern Standard Tribe

Eastern Standard Tribe Chicken Little

Chicken Little I, Row-Boat

I, Row-Boat Makers

Makers Rapture of the Nerds

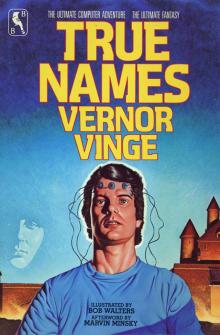

Rapture of the Nerds True Names

True Names