- Home

- Cory Doctorow

Someone Comes to Town, Someone Leaves Town Page 12

Someone Comes to Town, Someone Leaves Town Read online

Page 12

goblin toldus that he took off his clothes and waded in and started whispering."Like most of the boys, George had believed that their father was mostaware in his very middle, where he could direct the echoes of thewater's rippling, shape them into words and phrases in the hollow of thegreat cavern.

"So the goblin saw it happen?"

"No," Frederick said, and Edward began to cry again. "No. George askedhim for some privacy, and so he went a little way up the tunnel. Hewaited and waited, but George didn't come back. He called out, butGeorge didn't answer. When he went to look for him, he was gone. Hisclothes were gone. All that he could find was this." He scrabbled to fithis chubby hand into his jacket's pocket, then fished out a little blackpebble. Alan took it and saw that it wasn't a pebble, it was arotted-out and dried-up fingertip, pierced with unbent paperclip wire.

"It's Dave's, isn't it?" Edward said.

"I think so," Alan said. Dave used to spend hours wiring his dropped-offparts back onto his body, gluing his teeth back into his head. "Jesus."

"We're going to die, aren't we?" Frederick said. "We're going to starveto death."

Edward held his pudgy hands one on top of the other in his lap and beganto rock back and forth. "We'll be okay," he lied.

"Did anyone see Dave?" Alan asked.

"No," Frederick said. "We asked the golems, we asked Dad, we asked thegoblin, but no one saw him. No one's seen him for years."

Alan thought for a moment about how to ask his next question. "Did youlook in the pool? On the bottom?"

"*He's not there!*" Edward said. "We looked there. We looked all aroundDad. We looked in town. Alan, they're both gone."

Alan felt a sear of acid jet up esophagus. "I don't know what to do," hesaid. "I don't know where to look. Frederick, can't you, I don't know,*stuff* yourself with something? So you can eat?"

"We tried," Edward said. "We tried rags and sawdust and clay and breadand they didn't work. I thought that maybe we could get a *child* andput him inside, maybe, but God, Albert, I don't want to do that, it'sthe kind of thing Dan would do."

Alan stared at the softly glowing wood floors, reflecting highlightsfrom the soft lighting. He rubbed his stocking toes over the waxy finishand felt its shine. "Don't do that, okay?" he said. "I'll think ofsomething. Let me sleep on it. Do you want to sleep here? I can make upthe sofa."

"Thanks, big brother," Edward said. "Thanks."

#

Alan walked past his study, past the tableau of laptop and desk andchair, felt the pull of the story, and kept going, pulling his housecoattighter around himself. The summer morning was already hotting up, andthe air in the house had a sticky, dewy feel.

He found Edward sitting on the sofa, with the sheets and pillowcasesfolded neatly next to him.

"I set out a couple of towels for you in the second-floor bathroom andfound an extra toothbrush," Alan said. "If you want them."

"Thanks," Edward said, echoing in his empty chest. The thick rolls ofhis face were contorted into a caricature of sorrow.

"Where's Frederick?" Alan asked.

"Gone!" Edward said, and broke into spasms of sobbing. "He's gone he'sgone he's gone, I woke up and he was gone."

Alan shifted the folded linens to the floor and sat next toEdward. "What happened?"

"You *know* what happened, Alan," Edward said. "You know as well as Ido! Dave took him in the night. He followed us here and he came in thenight and stole him away."

"You don't know that," Alan said, softly stroking Edward's greasy fringeof hair. "He could have wandered out for a walk or something."

"Of course I know it!" Edward yelled, his voice booming in the hollow ofhis great chest. "Look!" He handed Alan a small, desiccated lump, like ablack bean pierced with a paperclip wire.

"You showed me this yesterday --" Alan said.

"It's from a *different finger*!" Edward said, and he buried his face inAlan's shoulder, sobbing uncontrollably.

"Have you looked for him?" Alan asked.

"I've been waiting for you to get up. I don't want to go out alone."

"We'll look together," Alan said. He got a pair of shorts and a T-shirt,shoved his feet into Birkenstocks, and led Edward out the door.

The previous night's humidity had thickened to a gray cloudy soup, swiftthunderheads coming in from all sides. The foot traffic was reduced tosparse, fast-moving umbrellas, people rushing for shelter before thedeluge. Ozone crackled in the air and thunder roiled seemingly up fromthe ground, deep and sickening.

They started with a circuit of the house, looking for footprints, bodyparts. He found a shred of torn gray thrift-store shirt, caught on arose bramble near the front of his walk. It smelled of the homey warmthof Edward's innards, and had a few of Frederick's short, curly hairsstuck to it. Alan showed it to Edward, then folded it into the changepocket of his wallet.

They walked the length of the sidewalk, crossed Wales, and began toslowly cross the little park. Edward circumnavigated the little cementwading pool, tracing the political runes left behind by the Market'scheerful anarchist taggers, painfully bent almost double at his enormouswaist.

"What are we looking for, Alan?"

"Footprints. Finger bones. Clues."

Edward puffed back to the bench and sat down, tears streaming down hisface. "I'm so *hungry*," he said.

Alan, crawling around the torn sod left when someone had dragged one ofthe picnic tables, contained his frustration. "If we can find Daniel, wecan get Frederick and George back, okay?"

"All right," Edward snuffled.

The next time Alan looked up, Edward had taken off his scuffed shoes andgrimy-gray socks, rolled up the cuffs of his tent-sized pants, and waswading through the little pool, piggy eyes cast downward.

"Good idea," Alan called, and turned to the sandbox.

A moment later, there was a booming yelp, almost lost in the roll ofthunder, and when Alan turned about, Edward was gone.

Alan kicked off his Birks and splashed up to the hems of his shorts inthe wading pool. In the pool's center, the round fountainhead was atwisted wreck, the concrete crumbled and the dry steel and brassfixtures contorted and ruptured. They had long streaks of abraded skin,torn shirt, and blood on them, leading down into the guts of thefountain.

Cautiously, Alan leaned over, looking well down the dark tunnel that hadbeen scraped out of the concrete centerpiece. The thin gray light showedhim the rough walls, chipped out with some kind of sharp tool. "Edward?"he called. His voice did not echo or bounce back to him.

Tentatively, he reached down the tunnel, bending at the waist over therough lip of the former fountain. Deep he reached and reached andreached, and as his fingertips hit loose dirt, he leaned farther in andgroped blindly, digging his hands into the plug of soil that had beenshoveled into the tunnel's bend a few feet below the surface. Hestraightened up and climbed in, sinking to the waist, and tried to kickthe dirt out of the way, but it wouldn't give -- the tunnel had caved inbehind the plug of earth.

He clambered out, feeling the first fat drops of rain on his bareforearms and the crown of his head. *A shovel*. There was one in thelittle coach house in the back of his place, behind the collapsed boxesand the bicycle pump. As he ran across the street, he saw Krishna,sitting on his porch, watching him with a hint of a smile.

"Lost another one, huh?" he said. He looked as if he'd been awake allnight, now hovering on the brink of sleepiness and wiredness. A roll ofthunder crashed and a sheet of rain hurtled out of the sky.

Alan never thought of himself as a violent person. Even when he'd had tothrow the occasional troublemaker out of his shops, he'd done so with analmost cordial force. Now, though, he trembled and yearned to takeKrishna by the throat and ram his head, face first, into the column thatheld up his front porch, again and again, until his fingers were slickwith the blood from Krishna's shattered nose.

Alan hurried past him, his shoulders and fists clenched. Krishnachuckled nastily and Alan thought he knew who got the job of sawing offMimi's wings when they grew to

o long, and thought, too, that Krishnamust relish the task.

"Where you going?" Krishna called.

Alan fumbled with his keyring, desperate to get in and get the keys tothe coach house and to fetch the shovel before the new tunnels under thepark collapsed.

"You're too late, you know," Krishna continued. "You might as well giveup. Too late, too late!"

Alan whirled and shrieked, a wordless, contorted war cry, a sound fromhis bestial guts. As his eyes swam back into

Pirate Cinema

Pirate Cinema Walkaway

Walkaway Little Brother

Little Brother Someone Comes to Town, Someone Leaves Town

Someone Comes to Town, Someone Leaves Town The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow

The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow Super Man and the Bug Out

Super Man and the Bug Out For the Win

For the Win A Place so Foreign

A Place so Foreign Shadow of the Mothaship

Shadow of the Mothaship Return to Pleasure Island

Return to Pleasure Island Party Discipline

Party Discipline Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom

Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom Lawful Interception

Lawful Interception Homeland

Homeland Eastern Standard Tribe

Eastern Standard Tribe Chicken Little

Chicken Little I, Row-Boat

I, Row-Boat Makers

Makers Rapture of the Nerds

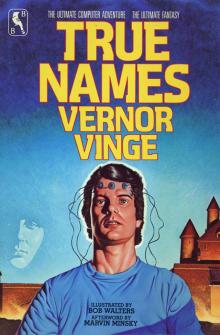

Rapture of the Nerds True Names

True Names